Art and law might seem like polar opposites. But in the wake of Conceptual Art’s challenge to the traditional operations of the art market, the law—and copyright in particular—has become an increasingly popular subject, and even a medium, for artists. Shane Burke investigates.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 30.

On the face of it, law and art appear to stand in contradistinction. The latter promotes an approach of art for art’s sake, privileged because it exhibits an expressive subjective creativity, free from the constraints of commercial reality. The law, on the other hand, is frequently seen as commercial and a bastion of objective certainty and conservatism. The judicial tendency to rely on public conceptions of what is artistic betrays a profound judicial unease at making aesthetic assessments in relation to works of art. As Costas Douzinas has noted, the law tends to only become accepting of new art after it has become conventional and habitual. Yet on further examination the law and art display unexpected commonalities.

It is perhaps in the context of the Conceptual Art movement and its programme of dematerialization of the traditional artwork and critique of the cultural system that one of the most thorough coalescings of law with artistic expression has been seen. Benjamin Buchloh, in his seminal article “Conceptual Art 1962–69: From the Aesthetics of Administration to the Critique of Institutions”, stated: “Because the proposal inherent in Conceptual Art was to replace the object of spatial and perceptual experience by linguistic definition alone (the work as analytic proposition), it thus constituted the most consequential assault on the status of that object: its visuality, its commodity status, and its form of distribution.”

Buchloh proceeded to acknowledge that, since the emergence of readymades, the designation of a work of art as such was primarily by means of legal definition and institutional validation, with the result that traditional notions of aesthetic judgement and taste were displaced by contract law and an institutional discourse. It was therefore in the context of such works that methods of legal validation ultimately became integral both to their form and in securing their status as works, and thus the use of contract law also became central to many artists’ practices.

“The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement” was developed by the dealer and curator Seth Siegelaub and the New York lawyer Robert Projansky between 1969 and 1971. This was a contract, designed to protect artists’ economic and authorial rights, which was easily understandable and reproducible, and was disseminated through journals and magazines. The contract further integrated the aesthetic and the legal by means of a “Notice” that was, if possible, to be physically fixed to the work (or, in the case of purely conceptual works, attached to their documentation), which it was intended would specify both its authorship and provenance, containing as it did the artist’s signature. It is also to be noted that should the authorship of the work in question be linked to copyright, the fact of this would render the “Notice” as a document indicating copyright. Alexander Alberro has stated that the importance of the artist’s signature on a legal document in signifying what the work was mitigated the effectiveness of the attack by the Conceptual Art movement on the cultural system as, irrespective of questions of form surrounding conceptual works, the presence of the artist’s signature on a contract enabled the effective marketing of ideas and the exclusive ownership of the work.

Daniel McClean has cited the “Artist’s Contract” as highlighting a “reflexive” relationship between art and law, where in the absence of real social transformation in terms of cultural production, works that incorporate contract law into their form instead reflexively highlight contradictions inherent in the production of art in a capitalist system. Yet despite these ambiguities, McClean does cite the Siegelaub and Projansky contract as hugely significant in terms of legal elements moving from being documentary in nature to actually moving to “within the frame” of many contemporary works. A number of contemporary artists have since continued this aesthetic engagement with the law, including Andrea Fraser, Lars Vilks, Jill Magid and the collective Superflex.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the increased interest in intellectual property in recent years, the seemingly ever-increasing scope of rights and a proliferation of publications relating to art and the discipline, a number of artists have begun to engage with copyright law as an integral aspect of some of their works. This interaction continues to demonstrate the aforementioned legal influence on artistic form and the reflexive nature of the relationship between art and law.

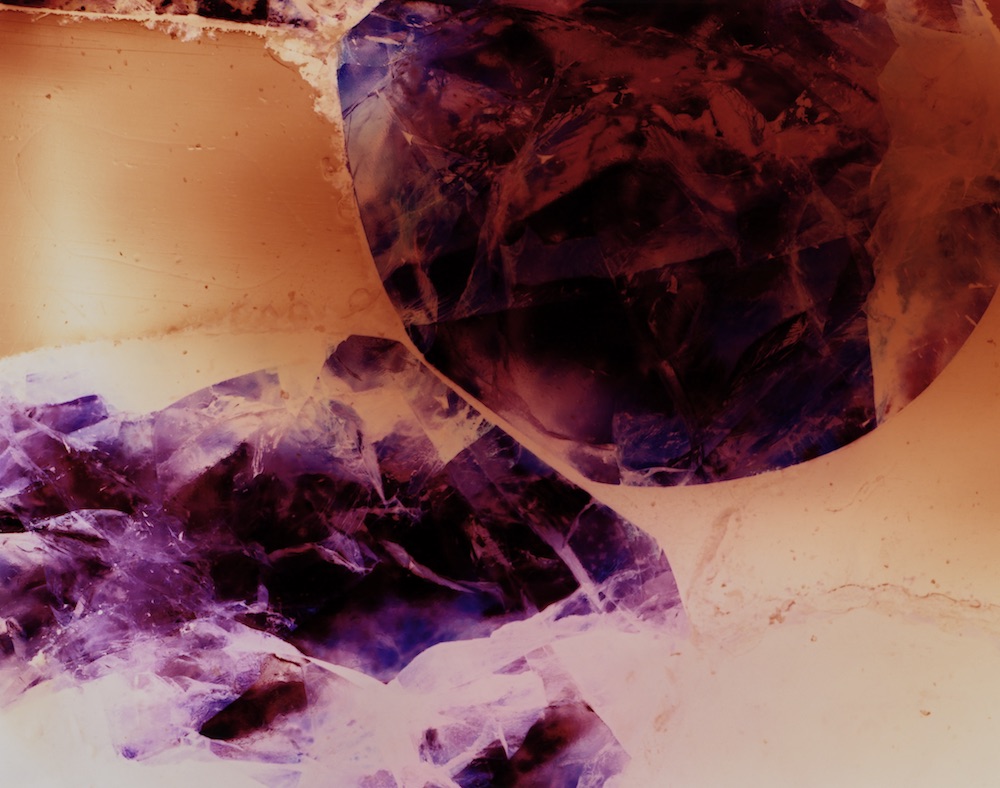

A recent example of a work where copyright is central to the artistic expression at hand is Carey Young’s elegant Redshift Series, which consists of six “camera-less” photographic images of fragments of a meteor which when purchased are accompanied by a declaration which states that from 1 January 2110 copyright in the said images will be abandoned on a country-by-country basis beginning at the Prime Meridian, this proceeding in a westerly direction across at a rate of 1,000 miles per annum as calculated from the Equator.

In terms of demonstrating the inherent reflexivity of the relation between art and law, the work of the Birmingham-based artist Antonio Roberts, whose recent works were exhibited at the Jerwood Space in London as part of its “Common Property” exhibition, provides an insight into the prospect of copyright as medium but also how the law and artistic practice may influence the form of each other.

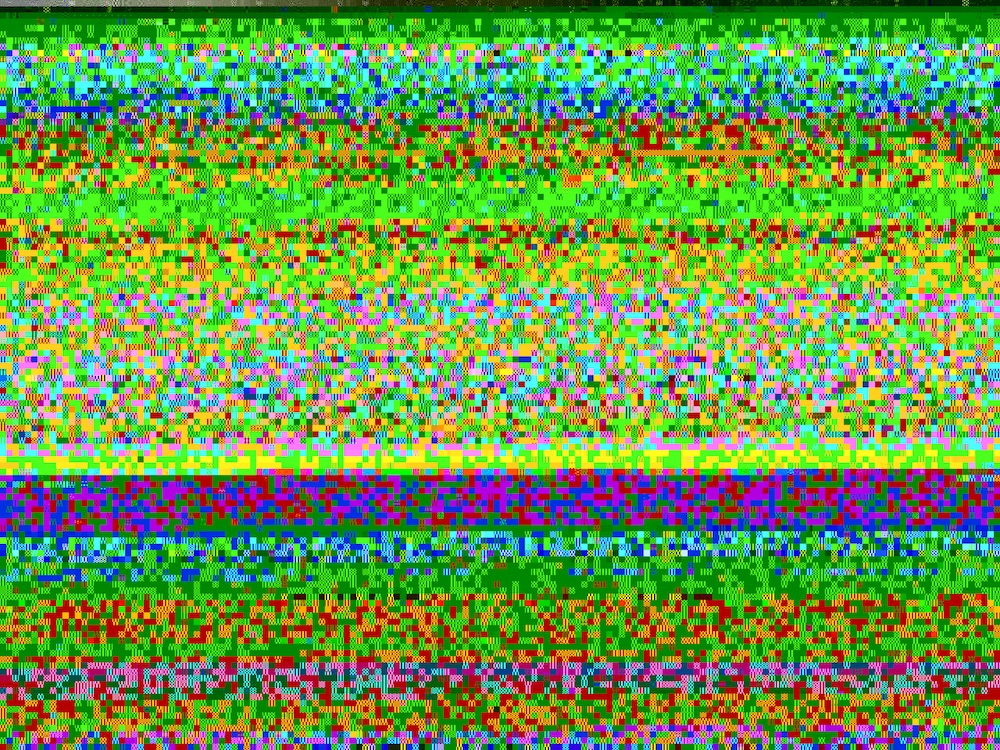

One of Roberts’s works features four musical tracks that have been the subject of copyright litigation including “Blurred Lines” by Robin Thicke, the subject of an infringement action taken by the family of Marvin Gaye in 2013 which resulted in the award of $7.4 million to the plaintiffs. Roberts uses self-developed software to convert each of the four tracks into visual works; this visual data is then in turn passed through another programme which converts it back into audio but in a fundamentally transformed form, unrecognizable in terms of the original piece. The artist thus flirts with the boundaries between what may constitute an infringing work and what is a transformative, and therefore potentially permissible, use of the work.

The fact that a work may involve a transformative use of another has become a critical factor in determining whether a fair-use defence to copyright infringement in the US will be successful for a defendant. The current law on copyright therefore plays a decisive role in the nature and form of Roberts’s work. On this point he states: “The piece is effective only as long as it pushes the boundaries of what is acceptable. As the laws change I would need to change the work to reflect this. Overall for it to be effective it needs to do the opposite of what is permitted by law. It is only by doing this, and highlighting how, quite frankly, stupid these laws are that I can hope to bring about change.”

Asked how he feels about the fact that copyright law may impact directly on the form of this works, Roberts averred: “I’m happy about it but it also confuses me. I’m annoyed by the fact that a change in law can physically alter the state of an artwork (e.g. if I were ordered to censor/cover up offending parts of the work) or change how it’s perceived. At the same time, if in doing this it can help to start a discussion around copyright laws then I’m happy to be a part of it.” When asked if he considered copyright law as an artistic raw material in terms of his work, he replied: “Yes, as long as law can physically alter the appearance of an artwork then law is something tangible that can be manipulated and worked with.”

While Roberts’s work is devised to instigate debate around, and change of, the current law on copyright, it is paradoxically consciously shaped by that law. However, it is also the case, and possibly again demonstrating the symbiotic relationship between art and law, that artists whose work engages in a dialogue with the current law on copyright are perhaps helping to shape that law. The line between what is considered infringing or not has been shifting to perhaps reflect a more nuanced understanding of contemporary artistic practice rather than the more usual conservative approach, grasping as it often does for familiar territory inhabited with notions of authorship and genius as defined by the Romantic movement or the strict formalism that characterized Modernism. The work of artists such as Jeff Koons and Richard Prince has led to a number of high-profile cases, which have arguably influenced the interpretation of the law on copyright in that they have pushed the boundaries of what may currently be considered transformative under the law in the US.

The possibility that US courts, in their determination as to what is or is not a transformative use, may engage in interpretations that evidence a more postmodern attitude influenced by the works of Koons (and, one could presume more recently, Prince) has in the past been explored by scholars such as Peter Jaszi. Yet it is important to note that the law has a tendency to retreat to familiar conservative pastures and the current interpretive approaches avoid bright line rules and are employed on a case-by-case basis and therefore may in time emerge as a passing phase rather than the inexorable future path for the law.

The employment of copyright as medium, perhaps the logical sequential step in the development of dematerialized artistic practice as handed down by the Conceptual Art movement, continues to raise interesting questions, not least of which is whether the reflexive relationship will ultimately lead to a change in the law or whether perhaps copyright, aside from its core functions, will simply continue to provide an interesting medium both to facilitate criticism and highlight contradictions and to influence form and expression in both the reified and conceptual realms.

Shane Burke is Lecturer in Intellectual Property Law at Cardiff University. He has recently submitted a doctoral thesis entitled “Dematerialisation and Dissonance: Conceptual Art Practices, Art World Strategies and the Role of Copyright Law” at Queen Mary, University of London. burkes3@cardiff.ac.uk