What can we expect from your current show at Maureen Paley?

I have chosen to present a combination of sculptural works, drawings and prints that focus on Britain’s history, national identity and the financial system. Much of my work as an artist draws on social history and I have taken three projects that explore these ideas through the lens of the 1920s and 1930s. I will be showing them together for the first time, as I’m interested to see how they can be read in relation to the political climate in Britain right now. The show references, on one hand, the British Empire Exhibition that took place in the west London suburb of Wembley in 1924, which can be understood as a propaganda event designed to bolster support for the British Empire and the system of trade that underpinned it. On the other hand, it highlights the response of two different social movements to the tumultuous conditions of that time: the Kibbo Kift Kindred and a journal called Urania, linked to the Suffragettes. There are some historical lessons and parallels to be drawn between the rise of nationalism after the financial crisis of the 1930s, and the relation between the current austerity politics, the rise of racism in Britain and the nationalist rhetoric that infected the whole Brexit campaign.

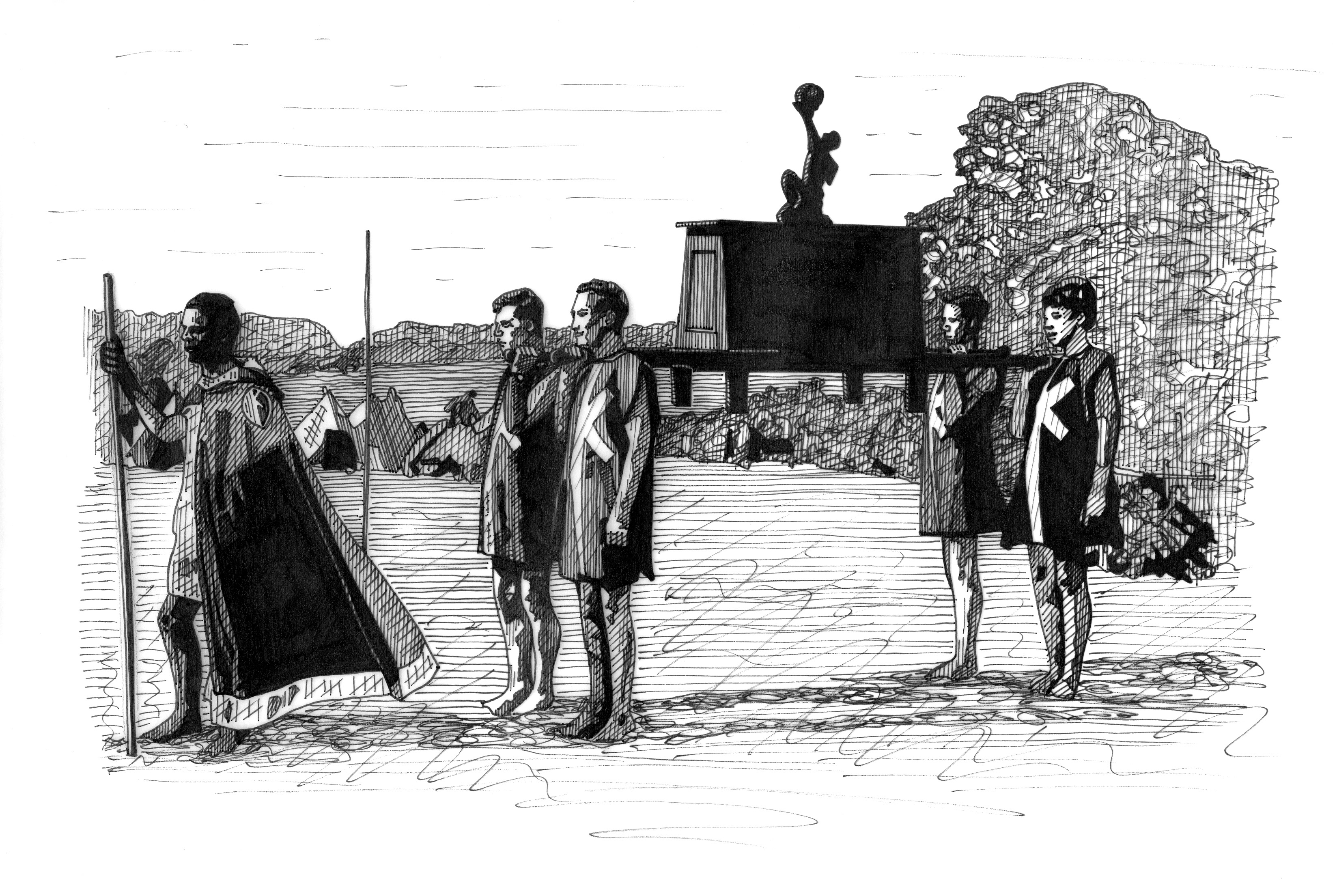

The Kibbo Kift Kindred were a British youth movement established in the 1920s by an artist and novelist named John Hargrave. Originally part of the Boy Scouts, the Kibbo Kift split from Baden Powell’s conservative organisation in order to establish a left wing youth movement, in collaboration with veterans of the Campaign for Women’s Suffrage and the Co-operative Movement. Inspired by the writings of Ernest Thompson Seton, as well as the Arts and Crafts movement, they were opposed to the ‘useless toil’ of the factory, adopting William Morris’s ideal of a return to a pre-industrial golden age. They were initially involved with such emancipatory causes as environmentalism, clothes reform, pacifism, vegetarianism and the democratisation of the arts, but were radicalised during the economic crisis of the 1930s into forming a single-issue political party advocating Social Credit – a now discredited monetary reform theory. Social Credit Theory outlined a plan for a universal basic income in order to free people from the necessity to work. It is interesting that ideas like the universal basic income, which were popular in the 1930s, are being discussed again today. However, it was at that time that the Kibbo Kift became a uniformed group (The Green Shirts), with a presence in the hunger marches and on the streets in many of Britain’s big cities. I made a number of works about the Kibbo Kift in 2008, when the contemporary financial crisis was first unfolding, and the drawings that will be shown in this exhibition are from that series.

You’ve picked up on this similarity between 1920s and 30s Britain, and Britain today. Do you feel the way those events were presented historically and culturally have shaped our thinking now?

In these kind of historical works I am interested in interrogating the ideological framework around the narration of history, who gets to tell the story of history and how. Many of the historical movements that I am interested in are rarely written about, or, like the Suffragette movement are very misrepresented. Therefore I present these kind of micro histories as a counter to the mainstream version of Britain’s history propagated by historians such as Niall Ferguson; who whitewash a lot of the brutality of the industrial period and British colonialism, in order to perpetuate an image of a liberal Britain that was ever marching towards progress. These versions of history have a huge impact on contemporary society, particularly when it comes to national identity and how we view the presence in Britain of anyone considered ‘other’ by mainstream society. I am very interested in interrogating ‘the voice of authority’ and looking at how ideas of ‘truth’ are constructed, whether by the media today or in mega events such as The British Empire Exhibition of 1924. Certain voices go unheard within the public realm, are considered illegitimate as they do not speak using the correct mode of address, or do not sound enough like those male, pale and stale Oxbridge educated voices that tend to hold power in the UK.

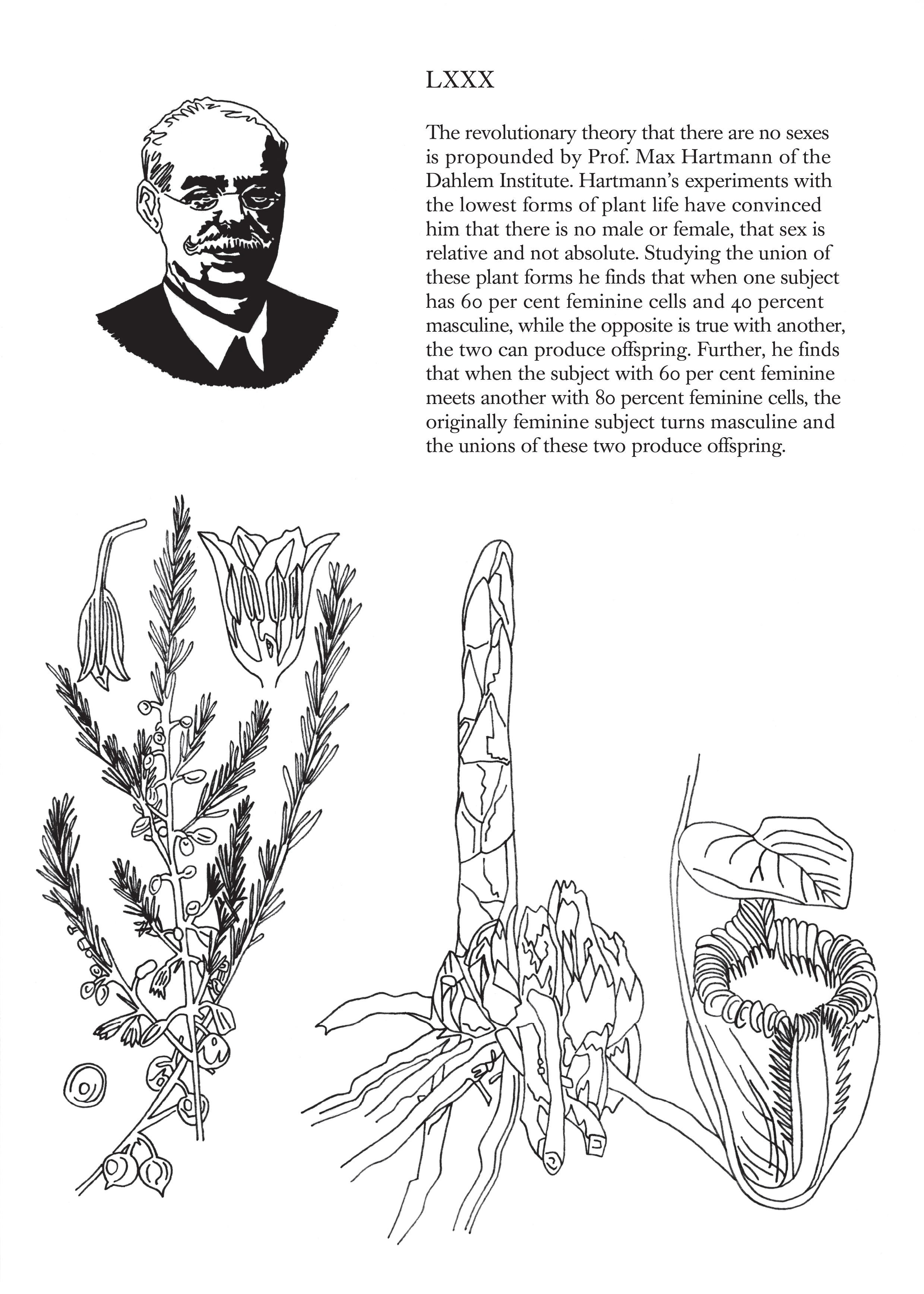

In direct contrast, the journal Urania is somehow poly-vocal. Urania ran from 1915 until 1940 and it was the first British magazine to produce a cultural and political discourse on gender issues and the demands of lesbian and gay individuals and communities. The name refers to a specific idea of Utopia, as a place where the categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’ do not exist. In the early twentieth century those people who did not neatly conform to social and sexual norms often referred to themselves as Uranians. Subsequently, the journal Urania was a kind of catalogue of incidents of gender troubling and feminist struggles, in the context of that time which included the rise of Fascism, Imperialism and the struggle by women for the vote. It was comprised of a collection of articles clipped from newspapers from around the world, which were re-published with very little editorial and analytical commentary, and distributed privately to a wide network of friends and supporters. Any commentary was often unsigned or published under a pseudonym used collectively by several writers, which made Urania into an ‘institution’ that constituted itself through a collective voice.

I came across the journal in the archives at the Women’s Library in London and when I started reading, one of the things that struck me was their internationalism. Urania published articles by and about feminist movements from around the globe, including Japan, Egypt, India and many countries in what we now refer to as the Global South. What is striking is that the journal existed during the same time period as the British Empire Exhibition, which represented non-western peoples as inarticulate and in need of Britain’s paternal guidance, but Urania presents us with women in the Global South articulating their own complex feminist struggles. The journal encouraged their subscribers to learn from these other struggles.

In recent years, I have been very interested in the misrepresentation of the Suffragette movement. Once I started researching it and looking at the diversity of the movement, groups such as that around Urania and also Sylvia Pankhurst and the East London Federation of Suffragettes in particular, it became clear to me that there are many aspects of the movement that have been suppressed by historians. The Suffragette movement was about more than winning women the vote. Much of what they were fighting for is still a problem for women today such as unequal pay, unequal division of labour within the family and sexual harassment. In many ways they were attempting to turn the whole world upside down, challenging norms such as the family and the gender binary itself.

You look directly at 21st century political issues in some works, notably in Stockholm Duck House: Proposed Monument to British Parliamentary Corruption, Circa 2009. Do you hope for these pieces to ignite further discussions around scandals that have been brushed under the rug, or is your main intention to simply analyse and explore the means of communication that surround them?

With the Stockholm Duck House I am very interested in highlighting corruption in the British Political system as it contrasts absolutely with Britain’s self-perception as a ‘civilised’ country that exported democracy around the world – the ‘mother of parliaments’. Right now it is particularly important to look at the state of our own democracy, as there is such wide-spread disillusionment with our parliamentary system. We are far from being a democratic country, because of the two party system and also the domination of parliamentary politics by certain class interests, who have allied themselves with the interests of big business. As became evident in the MPs expenses scandal of 2009, many MPs are still aristocrats. For example, Sir Peter Viggers MP inappropriately claimed money from the public purse for a replica of an eighteenth century Swedish building in which to house his ducks, as well as 28 tons of horse manure; his fellow Conservative Sir Douglas Hogg, 3rd Viscount Hailsham claimed the cost of cleaning the moat around his country estate. These details are ripe for satire, but a serious image also starts to emerge of a country that is stuck in the eighteenth century.

I am now planning to propose a new monument to corruption that would be called, ‘The Disgrace of Dr Fox: Proposed Monument to British Parliamentary Corruption Circa 2011’. This monument will depict a large bomb and will commemorate the actions of the disgraced former defence secretary Dr Liam Fox, who was forced to resign from the government in 2011 for allowing his friend and best man Adam Werrity to pose as his adviser. Werrity travelled the world meeting heads of state with Fox, taking the opportunity to advance his own ambiguous business interests, whilst pretending to work for the British government – whereas in reality he had no official parliamentary job and no security clearance. Although Fox lost his job at the time, it appears that there have been no serious consequences for him.

The works in the exhibition span a ten year time period. How have you felt your practice evolve since the creation of the earliest works?

Although in this show the emphasis is on works based on social history, one of the things that has happened in my art practice in recent years is that I found that I wanted to get out of the archive and collaborate with people. For example, at the moment I am developing a project with Open School East, working with different feminist groups active in London right now. The methods that we are using involve a lot of performance, as well as discussion, and are partially borrowed from consciousness-raising groups, which were a tool used by the Women’s Liberation movement in the 1970s. The conversations are often very personal, in line with the old feminist mantra ‘the personal is political’, thinking through the effects of political structures on our intimate daily lives, as well as what the Suffragette movement has to say to us now.

Can you tell me a little about the book that you’ve launched in line with the exhibition: Rise Early And Be Industrious?

Thematically the book mainly focuses on the projects that I have made on the theme of education and its relation to work, exploring different educational models from the industrial era until today. There are two opposing ideas that I am interested in contrasting: education as training for the workplace versus education as an emancipatory practice. For example, I think of world fairs and events such as the British Empire exhibition, as educational spaces designed to indoctrinate people into certain social behaviours. The British Empire Exhibition was embedded with norms around racial superiority, as well as competition, trade and the work ethic, which sociologist Max Weber famously linked to the development of industrial capitalism in his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. On the other side, there are examples of experimental education that emphasize playfulness as an interruptive to the rationalism of the factory and the soul destroying working conditions of the mechanized industrial era, creativity as the route to freedom. However a question arises in the book as to what these practices mean in the context of a post-industrial society, such as the UK, where many working practices have changed and ‘creativity’ is a quality that we are all now expected to bring into our work. The book reflects on these themes in essays by writers such as Tirdad Zolghadr, Lars Bang Larsen and Maeve Connolly. However, I also want it to be a useful collection of tools that other people can pick up and apply. There is a chapter focused on a summer school that I staged at the Banff Center in Canada, in 2010, called Beyond Former Heaven (or the Institute of Surrealist Ethnography), which is written as a set of instructions, a kind of ‘how to’ guide to running your own alternative school. In addition to which, the book includes a lot of the research behind my projects, such as interviews and archival material.

Olivia Plender is showing at Maureen Paley, London until 2 October.