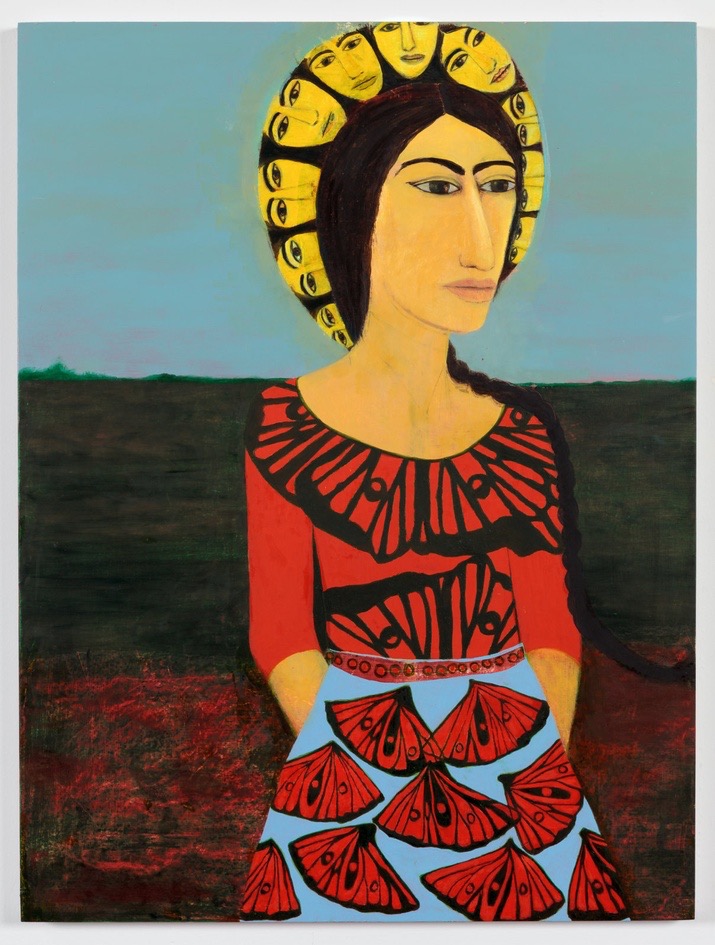

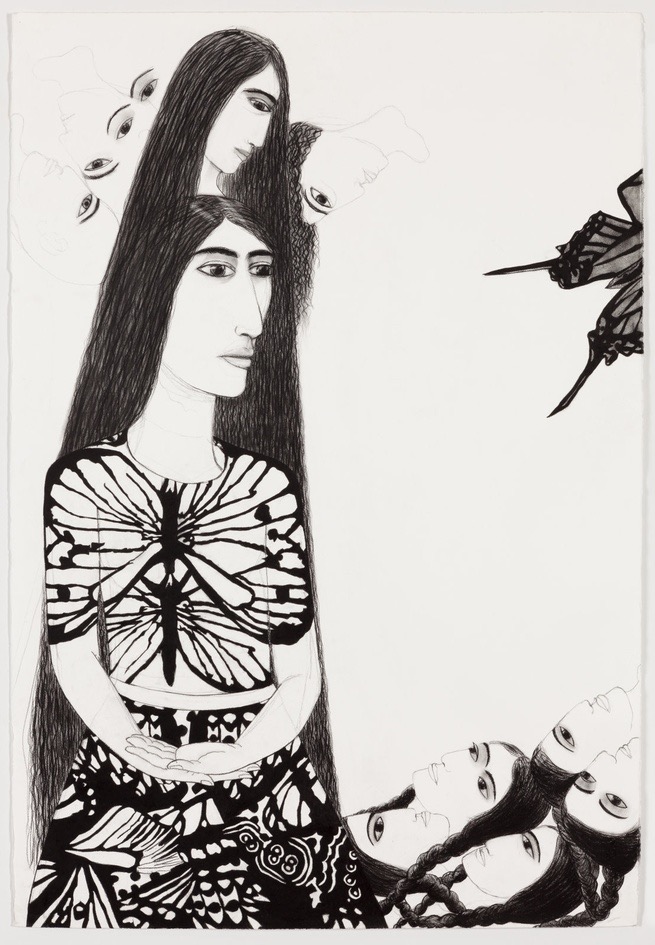

I reached the artist in New York during a ferocious electric storm that made the phone line crackle unpredictably as though we were participants in a strange séance. “We are made up of everyone who came before us,” she told me, referring to the female ancestors who—taken from Babylonian matriarchal cultures and Hindu iconography in relation to the goddess, Mother Kali—watch over the subjects of her paintings like spiritual doulas. They appear in the form of shrunken, wizened heads affixed to belts, shining in saintly halos, or even limp and doll-like in a lap.

Are these self-portraits?

Yes, but they are hopefully not narcissistic. They are not about me. My work is autobiographical but by accident. Because I’m a person living in this world at this time, I inevitably come up with subjects that are universal. I am painting different states that take place inside the body. I connect with Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious, which says our brain contains a hard drive which is the same in everyone and is filled with genealogical knowledge.

You’re sometimes compared to Frida Kahlo. Does that flatter or insult you?

I love her, but I feel like every time a brown woman paints a self-portrait, she is slapped with the Frida Kahlo label.

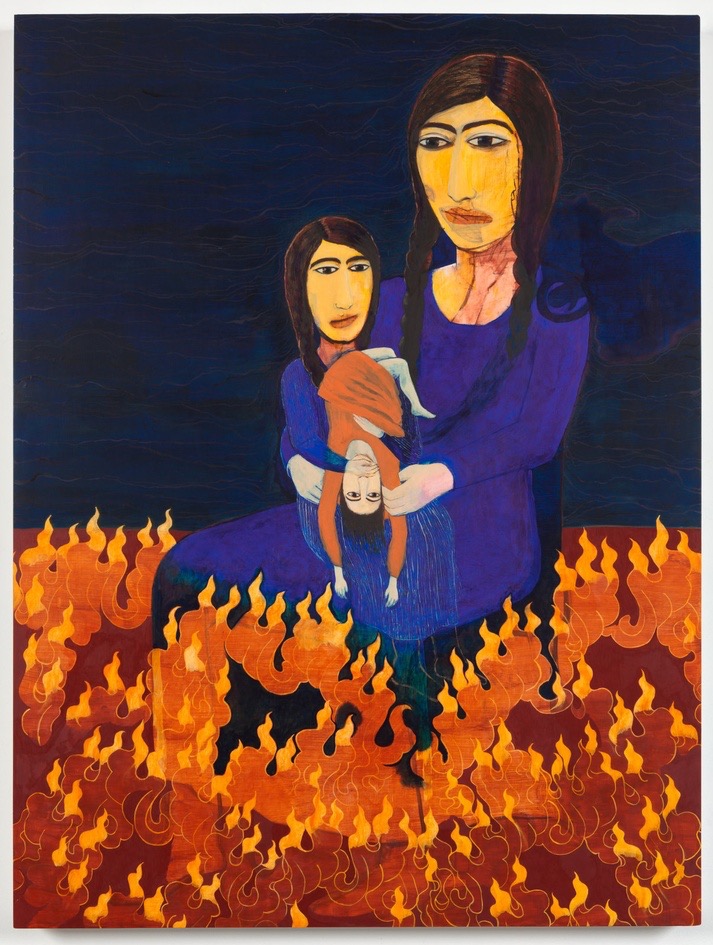

There is a surprising amount of violence directed at women happening here. In Reincarnated Fears and The Third of her Generation guns are pointing at women’s heads. Their forms are engulfed in flames. Why is all the conflict aimed at females in your work?

Other than one series, Eternal War (2011), I paint women because I am a woman. We are different—I can’t tell you exactly what it feels like to be a man. A woman contains a child or the possibility of a child and therefore she contains the male icon also. I paint about what I know the best. Women turn violence inwards and men make war.

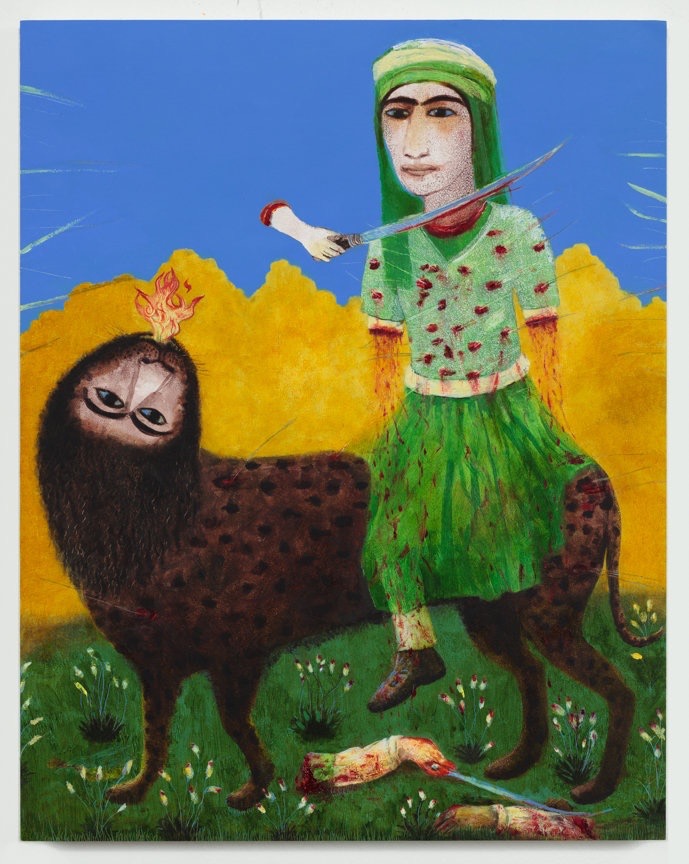

By trying to blur the distinctions between religions and civilizations, are you practicing a kind of cultural alchemy?

I’ve emigrated twice in my life. Once when I was two years old from Iran to England. Then I came to New York to open the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Studios in the 90s. I call myself a fictional historian because I come from a place that I’m supposed to know about and justify, yet I’ve never lived there. That is what has molded my work—a non-understanding of something I’m supposed to understand just by osmosis. Anytime you merge two different things you create something new. Culture, in its chemical sense, is something living that is constantly changing. That is what makes my work modern even though it’s almost medieval in its approach.

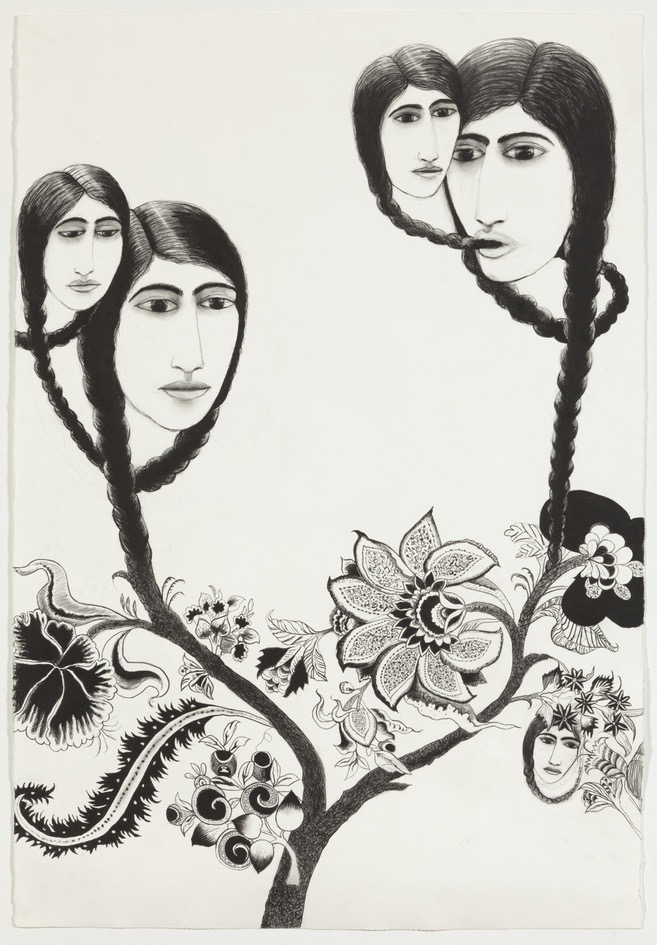

In Through Ingestion Grow Her Wings and many of your other paintings and works on paper, the female subject’s neck is encircled with a noose knotted with her own braid. Here she is actually ingesting it. You call this the umbilical braid. Where did that idea come from?

It relates to the snake in Kundalini iconography and in Medieval alchemy, it’s the symbol of wholeness with the snake swallowing its tail. It’s about swallowing yourself in order to absorb and process experiences. In this diptych and other places where the braid reappears, I am quenching the need I have both to express absolute horror and also to name something impossible.

This also goes back to my last visit to Iran when I was about twelve years old. There were two incidents: one with my maternal grandmother when, for the first time, I saw under her hijab, and there were these braids that were so involved that they twisted into little buns on the sides and just went on and on. They were orange from henna dye. For me, that’s a very powerful memory. That was her most intimate part and she showed it to me.

Another time, my female cousins and I bathed my paternal grandmother and combed out her braids. She had tattoos all the way down her chin to her belly button and her pubic area. The intimacy of seeing the markings of a body has stayed in the back of my mind. Even though they weren’t educated, my grandmothers had a sturdy knowledge that was transmitted in a very mysterious way. That is what I am trying to show in this work.

‘Redemptive Narratives and Migrating Patterns’ shows at XVA Gallery in Dubai until 25 May. xvagallery.com