It’s the end of the night at a club on the Po River. You’re wandering, lost, between crowds of drunk people from different places, talking in vaguely familiar languages, each group absorbed in their own frenzied agenda; to dance, to drink more, to get into the bathroom, to go outside to smoke—or in the case of this particular club, to do a line of roly polys down the dancefloor.

Being lost and alone in a club at 3am—unable to decide between which group to gravitate towards, feet sticking to the gummy floor, teeth licked with sugar—is what it feels like to live like a nomad, always observing, but never doing the roly polys.

We expect artists now to lead a transient life. A biography demands mention of at least three continents, between which the artist has been born, lived and worked (it’s interesting if the living and working take place on different continents). ‘Home’ has become ‘a base’—a word that implies temporariness, that doesn’t declare allegiance or commitment. What does it mean to live ‘between’ places, to abandon a homeland for a ‘base’, and how does it affect art?

“I think you can really see this nomadic life of the artist in the works,” says Sarah Cosulich, Artissima’s director. Geography, she told me, was important for the fair this year, but it was subordinate to the approach of the galleries. At Artissima, there are galleries from Guadalajara, from Sao Paolo, and Lima, who might represent artists from Dubai, China, or Slovenia, curated by researchers from Israel, Iran, Italy—it’s part of the cosmopolitanism of the contemporary art fair.

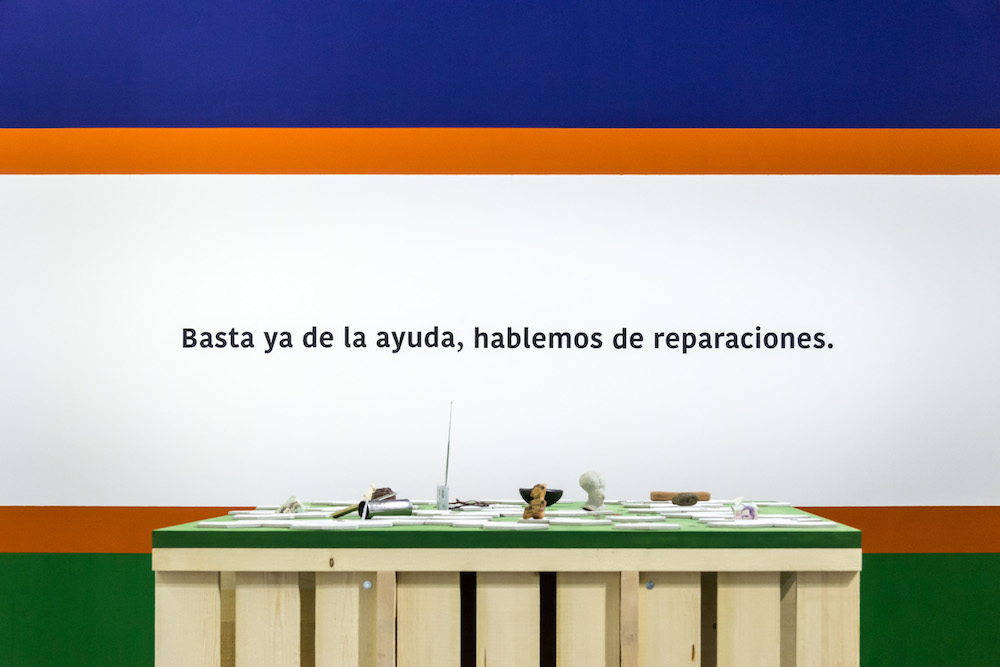

As someone who lives out of a suitcase, I understand there are both good and bad sides to moving around. An outsider’s eyes can observe in surprising ways, but the ease with which we can transition from place to place can also slip towards neocolonialism. Brazilian artist and researcher Beto Schwafaty, presented by Lucca’s Prometeo gallery, examines the recent history of exploitation in Latin America. An old found map, for example, depicts countries and their natural riches—not unlike guidebooks that suggest what you should go in and take away, rather than what you can leave behind.

The work of other artists—such as Domingo Milella—consider the distance and absence of the roaming heart. Milella’s series of photographs read as a yearning for the perfect place—but it’s the search itself that can often prove most painful. As Joan Didion once wrote, ‘one runs away to find oneself, and finds no one at home.’ Milella’s endless, empty landscapes are a journey; an attempt to identify with the earth, stripped back and bare, neutral, as it was before borders, politics and people.

Contrasting diametrically, in a new series of his funky eye-mask creations, Kenyan artist Cyrus Kabiru, presented by South Africa’s SMAC gallery, was inspired by a trip to Morocco, as well as research on ancient Nubia and the Caribbean—but sometimes, to live like a nomad doesn’t even require travel; sometimes the borders shift within you. Igshaan Adams, for example, contemplates his own cultural hybridity in his native Cape Town, where he grew up in the ‘coloured community,’ as a gay Muslim in his Christian grandparents’ home, and still lives today. Two sumptuous tapestries at Blank Projects—heavy with nylon rope, string, beads, and found fabric–are the material manifestation of working out all of these different parts of the artist’s life and surroundings.

The fundamental question of all art, after all, is: where do I belong?

I never found my friend at the club, but I did discover that where I belonged was in a taxi to the hotel.

‘Artissima’ runs from 4-6 November. artissima.it