In the months leading up to the artistic delirium that documenta14 promises to be, now moments away from being unleashed on a mostly unsuspecting Athens, a large number of artists have been busily working out of sight, with several hosted as artists-in-residence at various institutions across the city. One of the most notable of these is Atopos CVC, established in 2003 by Stamos Fafalios and Vassilis Zidianakis, which has successfully propagated certain facets of the contemporary visual scene in the city since its inception.

Three artists currently reside at Atopos: Ibrahim Mahama, Nevin Aladağ and Daniel Knorr. Though each have developed distinctive styles and working practices, they have found solace within the residency, and have drawn significantly from their stay for several months in Athens.

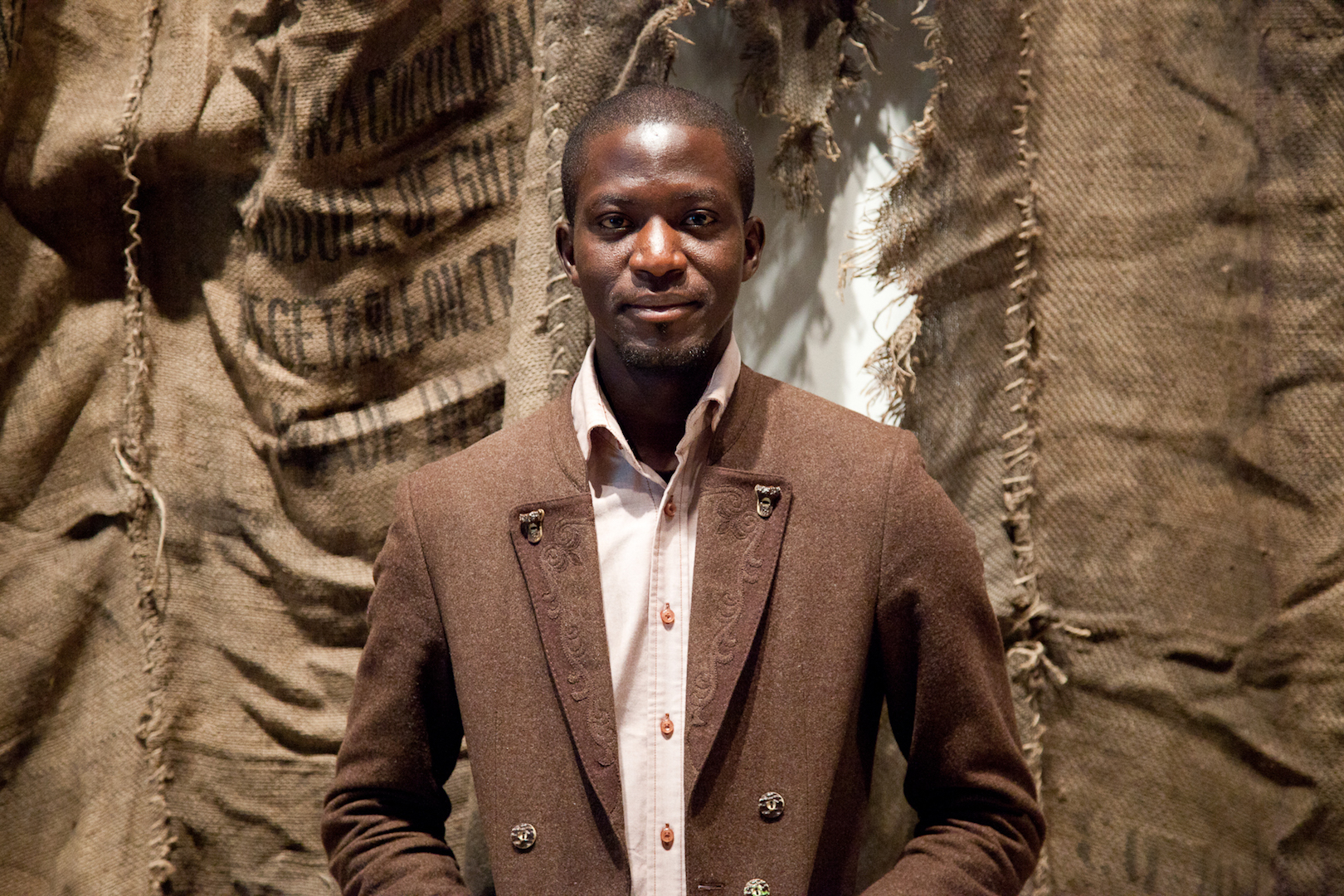

Ibrahim Mahama, an artist of Ghanaian origin, best known for his tapestries of jute coal sacks woven together and draped over buildings, chose to spend the majority of his time in Athens not at Atopos, but at a refugee housing project called Prosfygika. It was originally built in the 1930s to house Greeks who had fled genocide and persecution under Ottoman rule. Almost 100 years later this eight-building complex still continues to house refugees and others seeking shelter in times of economic hardship. From Greek occupants who have remained in the apartments for over 70 years and more recent foreign asylum seekers to local families forced to leave their existing homes and heroin addicts, the diverse population has developed a method of co-existing and working together. While living there, Mahama has participated closely with the community, paying close attention to the organisational structure, politics and character of the space, as well as the nuances of the various productive forces within the community such as writing, drawing and other communal work. Mahama tells me that he has used these everyday, life-sustaining processes as a point of departure for his own art making.

On several occasions prior to the official inauguration of the festival on 8 April 2017, Mahama has invited groups of Athenians to take part in performances in the city’s parliament square, Syntagma, each of which involve the sewing together, un-sewing and re-sewing, of large numbers of jute sacks. Mahama tells me that the significance of conducting this act in Syntagma Square draws focus to the political history of the disintegrating sacks: “The sewing of these materials in decay is a reminder of the history of production but also a form of protest simply by occupying the space temporarily.” Just as the material of the sacks breaks down over time as they are transferred from one use to another, the commercial history of the sacks is underpinned by a history of capitalism, itself in some ways nearing a point of collapse, as well as Greece’s and Athens’s location as a crucial center of international trade, extending back millennia. There is no plan to display the tapestries themselves during the festival, though some of the residue from the process will be exhibited in Kassel, which will inaugurate a branch of the festival on 10 June 2017.

Such residue is precisely what Daniel Knorr utilises for his main work produced during a four-month stay in Athens. Spending many days scouring the streets of the city and its outskirts, Knorr has collected over ninety 120-litre bags of detritus. Meticulously laying these out over his 100-square-metre studio space (“It’s nowhere near big enough!”), Knorr then undergoes a second round of selection during which he chooses the objects worthy of inclusion in the 1,100 Artist Books he is presenting as his work for the festival. Pressed between the pages of these books, these objects not only create embossed and debossed impressions, but also take part in a further urban narrative, and one that will, through the books’ sale alongside the official documenta14 ‘Reader’, fund a further work in Kassel. Knorr tells me that on his search, during which he was surprised to find objects like a loaded gun and a hand-written children’s book from 1938, the homeless community took him in as one of their own, often offering snacks and other gifts to acknowledge his presence among the other scourers of the urban landscape.

Knorr’s aim is that his “library of junk”, as he calls it, will be exhibited at the city’s National Archaeological Museum, to form a contemporary archive and one that could eventually be researched alongside his ‘libraries’ from cities like Bucharest, Los Angeles and Istanbul. “Though,” he says, “the objects I have found in Athens are the best!” The piece will likely also reflect Material Matters, a parallel educational program at the festival, whereby objects entrusted by various artists to EMST, the National Museum of Contemporary Art and the Athens School of Fine Arts will be explored by students in dialogue with various artworks. As the world seems to undergo a process of fragmentation, Knorr’s effort to piece together its “value-less” shards not only raises questions about the level of wastage in society today but is also a valiant investigation into the reasons for this global disintegration and our own national cultural identities.

Like Mahama and Knorr, Nevin Aladağ has also found Atopos conducive both to artistic contemplation and to cooperation. Just as Mahama helped Knorr find a production assistant, and suggested under-visited areas for his personal excavations, Aladağ chanced upon a nearby store of antique furniture, objects which she has used in her artworks, in the storage area found by Atopos for Knorr, Aladağ’s partner. Together with a number of craftsmen, Aladağ has constructed instruments from furniture and other household objects, encouraging the development of their own acoustic properties attributable to their shapes, often evoking the human body. In the process, prevailing notions of functionality, ergonomics and purity of sound are called into question, with the installation itself, Music Room (Athens), referring to historical music rooms that were once furnished as sites for the production of music at court, but also questioning the function of the furniture and hence cultural production in itself. On several occasions during documenta14 musicians will, for the first time, play the instruments of the Music Room at a space within the Athens Conservatoire.

These artists and this residency, each central to the inauguration of documenta14, represent but some examples of the cooperation that exists within Athens today. The success of the festival, and of Athens as a creative environment, continues to rely on such collaboration, thankfully a characteristic that has in some ways become a synonym for the city itself.

‘Documenta14’ runs from 8 April until 16 July. documenta14.de