Where have all the Mad Men gone? What would Rosser Reeves, 1960s marketing wunderkind and one of the inspirations behind the character of Don Draper, make of branding today? What is branding’s Unique Selling Point (a term Rosser coined) in today’s fluffy ‘content’ and ‘storytelling’ world of sponsored brand experiences, experiential themed shipping containers and latent marketing gurus, who espouse brand awareness to internet trolls through outreach craft communities of ‘maker-doers’? Robert Urquhart investigates.

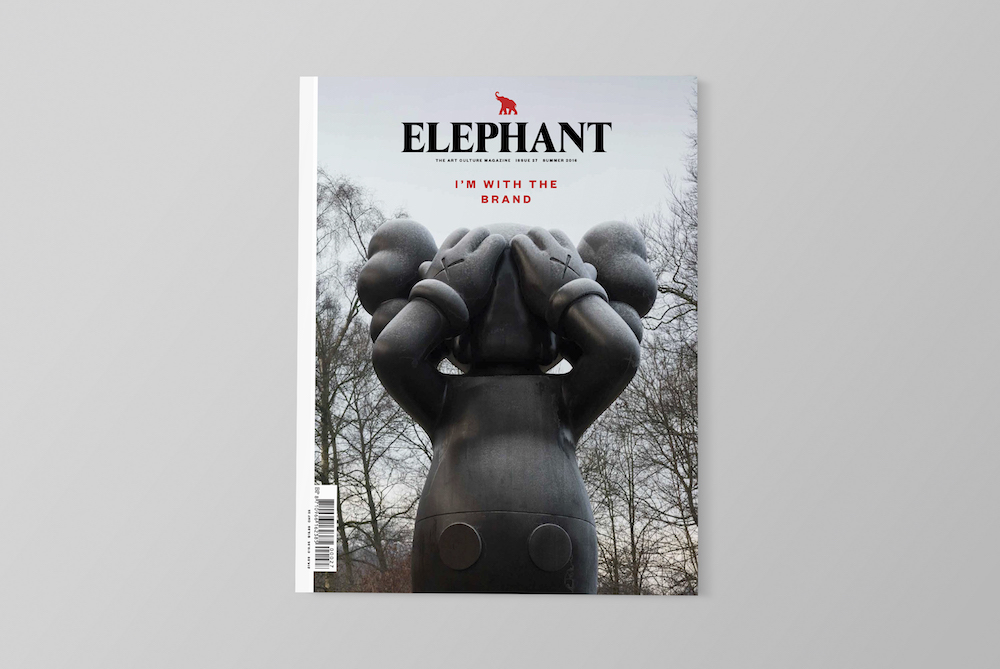

This feature originally appeared in Issue 27

I can almost hear Reeves choking back the scotch. Reeves wasn’t what you’d call ‘latent’. He believed in The Proposition. Branding and advertising weren’t passive or intuitive acts. Advertising was a demonstrative hectoring display of blind self-belief, carried out on behalf of the client, spurred on by the agency. Branding was the armour you wore while you crooned and twerked at the crowd.

And then something changed—most probably it was the internet. Who’s running the show now? What has ‘digital’ done to make advertising and branding so touchy-feely?

‘Marketing in the future has to rely on peer-to-peer inspiration,’ says George Gottl, CEO of UXUS, a partner of the global branding agency Futurebrand. UXUS ‘reinvent brands’ and create ‘desire’ for big names such as H&M, McDonald’s and Nike. ‘We actually look at the behaviour of people rather than going to agencies doing these in-depth analysis pieces, because often what happens is customers tell you one thing but they actually want something else.’

The comfort-blanket concept of ‘branding’ as design communicating through a one-way corporate lens has been shaken up in recent years. The expectation of the consumer revelling in a brand’s USP as conveyed through commercial design has evolved. Branding has grown into a multidimensional picture—a mosaic pattern built on real-life user experience as much as corporate brand ambition.

‘The market is changing dramatically,’ explains Gottl. ‘Big companies are very nervous, a lot of big companies have turned things upside down. Big companies that looked invincible years ago are now on shaky ground. A lot of things are now being flipped by the consumer.This is leaving companies afraid. Giants fall very easily—just look at Nokia, Kodak and Blackberry. There’s a whole graveyard of companies out there that fail to maintain the market innovation position.’

Gottl tells me about working on a new concept store for McDonald’s. The team at UXUS had been looking at the way the younger generations use street furniture in New York, in particular the type of tiered seating you might find in a sports venue or auditorium—stairs, essentially. Gottl had noticed that people were using tiers out of preference as it gave them the chance to look over each other’s shoulders at the phone screens that they were sharing ‘content’ on. ‘We get these insights and cues through the behaviour of the customer, and through observation we create something,’ says Gottl. ‘It’s an anthropological exercise.’

Gottl deployed tiered seating in a McDonald’s for the first time recently in a store in Leicester in England. A sceptical franchisee was converted overnight when she found the new approach a hit with the kids. ‘It’s about creating the stage for that experience to happen with the consumer. And when we build that stage, we are building in, not only the physical part, but also what we call the service model, which is the interaction or the rituals that go around the brand itself.

‘We might find a quirky way of opening a bottle or something unique that becomes a signifier, something that hopefully becomes a memorable code or cue for the brand,’ says Gottl. ‘So that when someone sees something similar they recall the experience, they recall the brand.’

It’s time to introduce Simon Whybray, a subversive character who makes branding agencies nervous: a child actor grown up in an internet-addled world, trained as a graphic designer, now constructing his life stage through the new prism of branding. For this generation, to be a graphic designer working with branding is to be tasked with writing the script for a polymorphous ‘design performance’. Visual imagery remains central, but simply creating a logo and a ‘feel’ is no longer enough to lead the charge—branding is now about fashioning a dialogue between user and client.

In the pursuit of branding, Whybray once convinced the world that he faked being the Pope on Twitter. He was Will Self on Twitter for nine months. He’s been on the cover of the NME dressed in a papal outfit—except he wasn’t, it was a Photoshop job. He has played in a band called TEETH, which may or may not have hijacked Lady Gaga’s Twitter account. He is a graphic designer. He doesn’t have a website (though he has a Tumblr) and he doesn’t have a portfolio. At the time of writing, I’m waiting for him to send images of his work to me. He’s in Los Angeles on his way to Austin, Texas, in a self-branded coach after putting on one of his JACK parties.

Whybray is a one-man brand.

The first thing he shows me when I visit him, at his home in London, is an inscription in a large tome: The Collected Works of ‘The Far Side’, a present that he received on leaving his first job at the branding agency Perfect Day in London in 2007. The inscription, along with all the other bons mots and best wishes from co-workers, reads: ‘You leaving? No idea. Keep up the good YouTube.’ These barbarous but good-humoured words were penned in recognition of Whybray’s fondness for surfing the web when he should have been doing his ‘proper job’.

Whybray’s proper job was to help brand the political party that would be the main partner in the next uk government, the Conservatives, and, after they won, Boris Johnson, when he ran for (and was duly elected) mayor of London.

Aside from short periods freelancing for creative agencies including Mother London, Moving Brands, Futurebrand, Getty Images and Build, Whybray has been branding a website for super-star dj and producer Skillrex and, most recently, has designed a book for Los Angeles-based artist Michael Manning entitled 100 Paintings.

Do you have to know your subject to work with them? ‘I don’t think I used to, I think I do now,’ says Whybray. ‘I want to see what shoes they are wearing. I want to know what they’re going to do for five years, even if that has no bearing on it.

‘I’m helping brand Skrillex’s media platform right now and they sort of just want a logo but the way my work sort of works is that the logo really isn’t anything on its own. It needs to be there to remind people what “the thing” is. The experience of the logo isn’t the brand, it’s just a thing to fill a box.’

The main creative outlet for Whybray over the past two years has been his ‘non-stop-pop’ club night called JACK.

‘It’s what I’ve become,’ notes Whybray. ‘It’s given me the opportunity to experiment graphically. JACK gives me an opportunity to tell people about something twice a month. I have to start finding ways to keep things fresh and show that a lot of stuff is happening. I’m creating a graphic language here.’

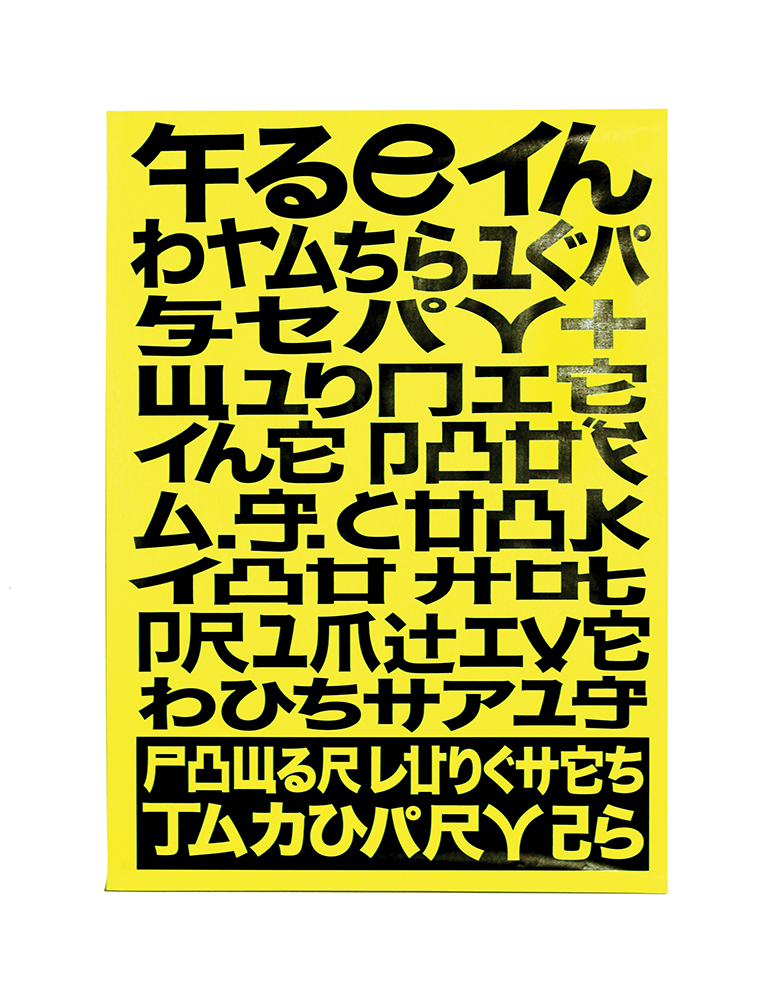

Whybray brings out a poster. ‘Every show has one colour and each show has a membership card. It’s a club, it’s a clan. I think the lesson here is to always plan on going to each non-stop-pop event without question—that’s the brand. That’s the way I promote, by doing it really correctly, by surprising people that I’m flying in and giving them the tools to be excited.’

Is this stance of ‘plan so that people follow the brand without question.’ Whybray’s mantra? ‘I learnt all this from faking other things. Remember when I was the Pope on Twitter? I wasn’t the Pope on Twitter, it was fake on fake on fake.What I learnt from that was that everyone needs to be laughing at each other. JACK is people dancing at each other. It’s about giving everyone the tools. Basically, you are doing things that make sense in the right order. What’s fun, and hard to communicate, is that I’m branding myself through branding everyone else.’ Looking for people to put Whybray’s work in context, I visit Kate Moross at her studio in South London. Moross and Whybray are friends and occasionally work together. When I visit the studio has been helping out with some animation for the JACK club night. Is Whybray a brand? ‘That’s exactly what he is like. Simon is a new-media hippy,’ laughs Moross. ‘Simon and I are about the same age, social media emerged with us and we feel like we established them. Simon has the ability to tap into that thing of wider memes and wider stories and then create a piece of work that celebrates it or laughs at it or traps and tricks people. He’s into the zeitgeist and wants to create it. I think he understands brands and how to make a brand rich and full of detail that people can adopt and enjoy. It’s not like a single-sided entity.’

I talk to James Bull, co-founder of Moving Brands, an agency set up in 1998 by three Central Saint Martins graduates that now has offices in London, San Francisco, Zurich and, most recently, New York. Working under the banner of ‘stories, systems and experiences’, the company continues to plough new ground in branding innovation.

We start talking about music and culture. ‘No one starts out wanting to be a graphic designer, it’s where you end up with your creative talent,’ says Bull, wryly and sincerely. ‘It’s about understanding tribes and what they are. The world of communications and branding often thinks about people as a node that is able to say “yes” and “no”, but people are full of all kinds of things that they don’t really talk about, like the hidden self versus the real self. It’s all about understanding people.’

How do you brand a branding agency? ‘We got [London design agency] Bibliothèque to do our identity,’ says Bull. ‘I’ve never seen an agency do its own branding and manage to make it look good: You can be too self-indulgent and give it too much time or not give it enough time, so the idea of going through the branding process ourselves didn’t appeal. But because we were very intuitive people we very quickly got to an agreement, and brought it to life.’

What would Moving Brands do differently now on self-branding? ‘Bibliothèque did such a good job, and we’ve had our logo in the market for so long now, that I’d be of the opinion that if we had to reinvent I’d like to turn the company into a brand in its own right. I think Moving Brands could turn itself from being an agency that delivers things to a client to being a creator of our own products and digital experiences that customers want to buy. I’ve often joked that if we wanted to make a better phone than Apple we could. It’s just a matter of time and money.’

Just a simple matter of time and money. Isn’t it dangerous for poacher to turn gamekeeper? ‘We’re not talking about sneakers,’ says Bull. ‘We are talking about little r&d tools that can be productized. All I’m saying is that I think Moving Brands is the type of agency that if we did do that our own industry would look at it and go: “It makes sense that Moving Brands could go down that route.”’

Back to George Gottl. ‘I was reading about a new product by Amazon, called Echo, which is basically an artificial intelligence machine that you can talk to and it will do things for you,’ says Gottl. ‘Amazon cannot keep these in stock as they are just too popular.That says a lot about where the future is going: that even the machine itself will become invisible, so branding is actually even more about a tangible feeling and aspect of something, because a very nondescript nothing of a machine can hear you and respond to what you want. Echo talks back to you; all you hear is a voice, you don’t even really have a physical object to interact with, and yet it’s an important thing that actually takes care of your life.