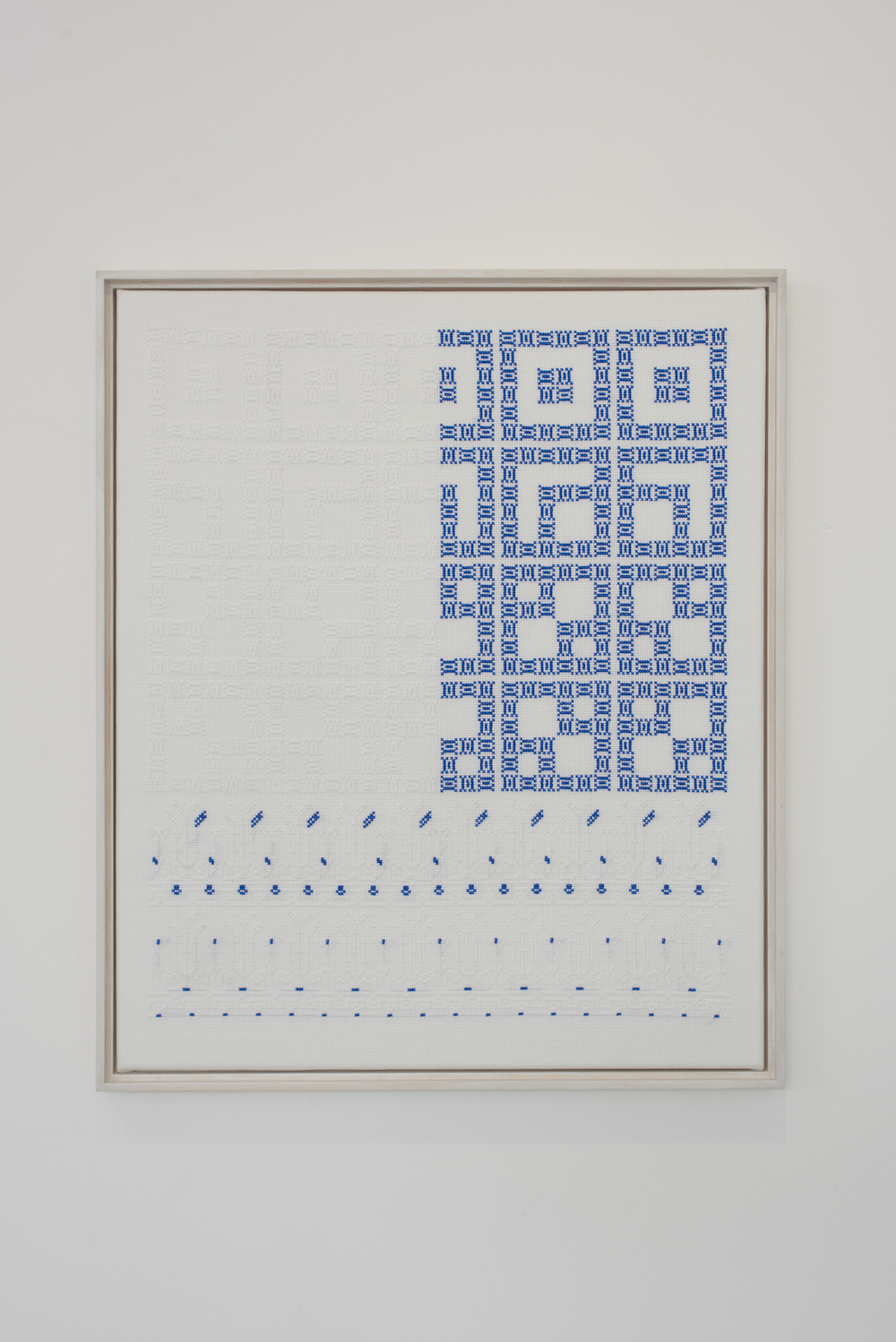

New York-based artist Jordan Nassar explores cultural absorption and his own Palestinian heritage by engaging with the country’s tradition of embroidery. His labour-intensive works (each piece contains up to 75,000 individual stitches) also draw their motifs from technology and the computer screen. ‘Cross-stitch is, in a way, the first pixellation,’ he tells Molly Taylor.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 28

Nassar doesn’t only make art—he also maintains managerial roles at Printed Matter (NY’s coolest artist book and zine shop), the ny and la Art Book Fairs, and LA’s ever-expanding annual fair Art Los Angeles Contemporary (ALAC). ‘The best thing about [my jobs] is being surrounded by amazing, inspiring artists all the time,’ he says. ‘That being said, I am really, really busy.’

Your first solo show was at Evelyn Yard last year. How has your practice developed since then?

I’ve decided to take the work in a more political direction. The exhibition in September is focusing on the notion of what I call ‘cultural absorption’ and questions such as: When something is introduced into a culture by outsiders, how long does that thing have to exist within the new culture before it is forgotten (or at least unimportant) that it originally came from elsewhere? How many things in all of our cultures are actually footprints from other cultures? And can culture be part of the land rather than an attribute of the society? In my imagination, the longer Israel is where it is, for example, the more it becomes a Middle Eastern country, as opposed to the Eurocentric one envisioned by its founders.

So you think of your work as political?

I do indeed think of it as political and I have, in fact, been making an effort to make it more explicitly so. I think it’s really important for someone in my position—a Palestinian-American married to an Israeli. I don’t necessarily agree with this phenomenon, but in our society people get very quickly up in arms if someone makes work that addresses an issue that isn’t ‘theirs’. I see a lot of fuss about ‘ownership’ of issues, and defensiveness over it. I don’t love that that happens, but I feel as a Palestinian/Israeli of sorts, it is my responsibility to use that ‘card’ and to make work about it. I just feel like, if I don’t—me, someone with family on both sides, who identifies with both sides—who will? I do feel that I was born into the conflict, and my whole life it has been a source of anxiety for me. By marrying an Israeli, I have committed to it as a part of my life. It’s a process of opening up to it, letting it in and actually grappling with it, actually letting myself care about it, read about it, go and visit more and more, get political about it and, of course, make work about it.

You’ve said that the elevator pitch for your work is that it ‘addresses the intersection of craft, language, history, (geo) politics, and technology’. How do you use technology? What are you referencing?

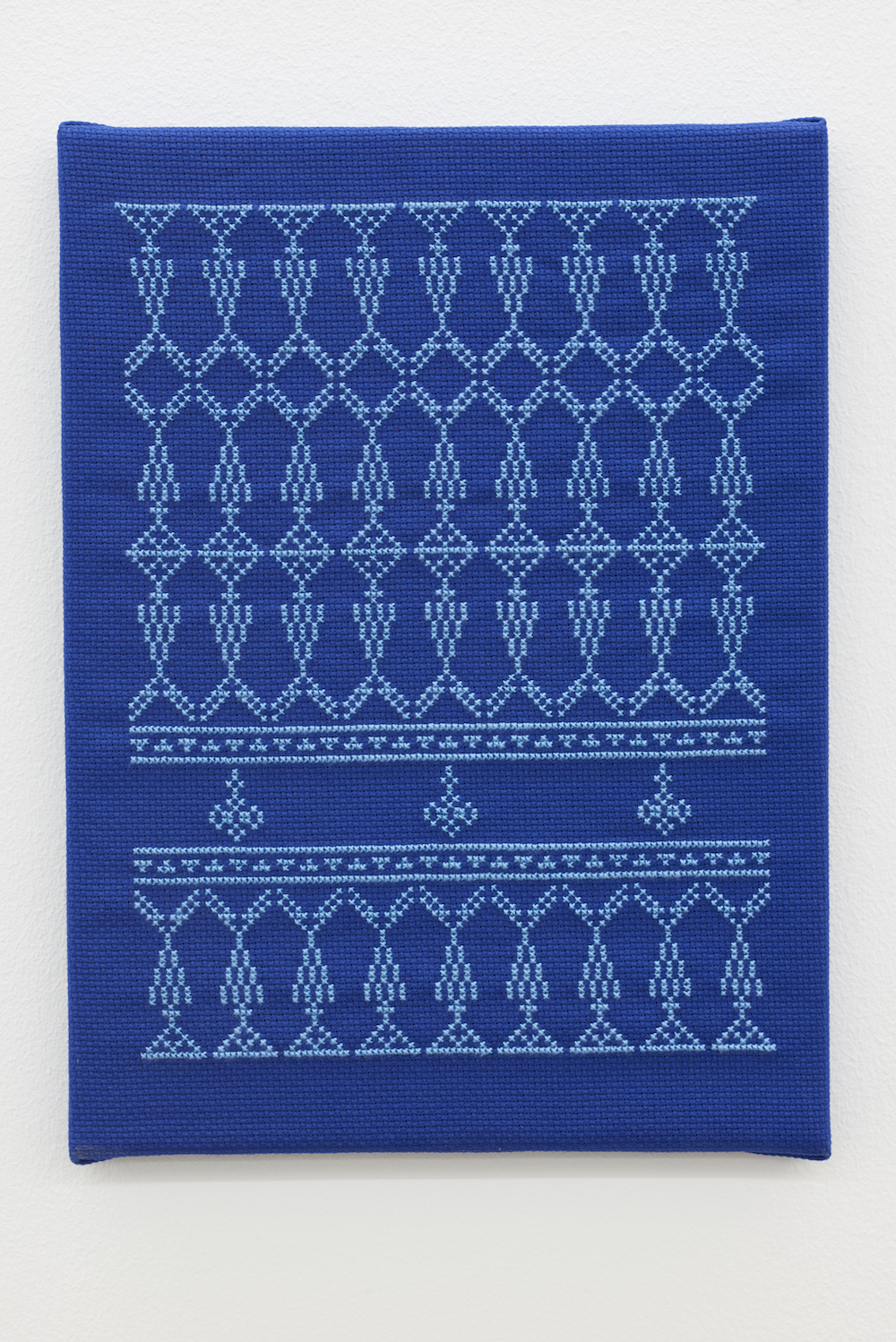

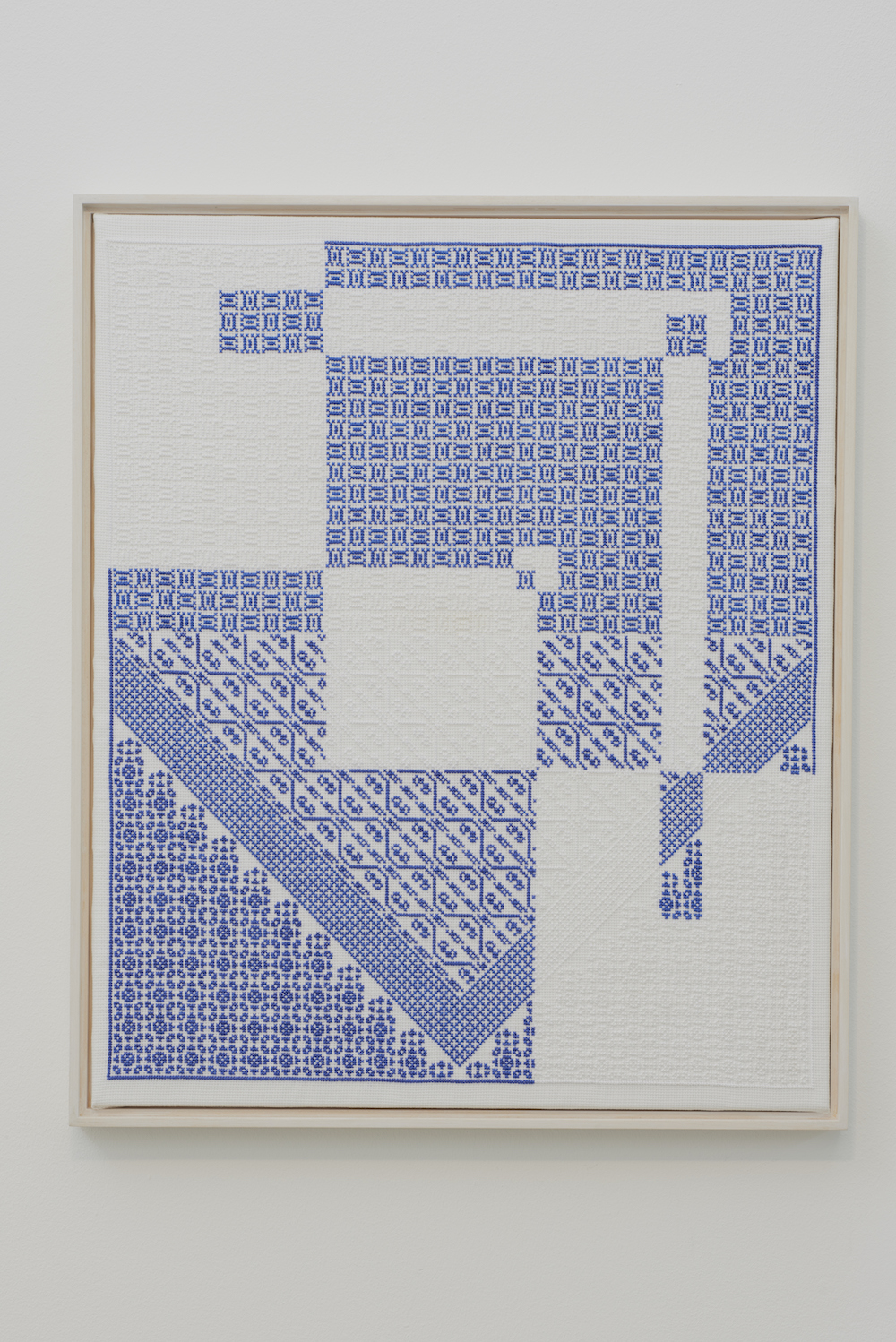

The pixel! The pixel has been so hot lately, and cross-stitch is, in a way, the first pixellation. But Palestinian traditional embroidery is interesting because there is a clear dividing line, a turning point in history, between pre-European and post-European Palestinian embroidery. Before the Europeans came, the traditional embroidery was very fitting with the medium—lots of squares, rectangles, lines and triangles used in a completely abstract way to represent everyday things such as geographical features of the land. After the Europeans showed up in the 1800s, you start seeing floral motifs that are figurative—trying to capture real-life images in a rigid medium, resulting in that ‘pixellation’ look. This also led me to the question I mentioned before—now that the Palestinians have been using these Euro-patterns for hundreds of years, are they Traditional Palestinian Patterns yet?

You’ve also produced some heat-sensitive works. Can you tell us about them?

The heat-sensitive works were actually inspired by some early viewers of my embroidered work who wondered how best to keep them and whether they might fade in the sun etc. I thought long and hard about it—did I want them behind glass? Plexi? Something? And then I thought about textiles and how they carry their lives with them—how this blanket is special because your grandma made it, or whatever—and thought that no, we should present them unprotected, just on canvas or maybe with a wooden tray frame. Anyway, the heat-sensitive ink on paper was an editioned series addressing that—they are blue when cool, fade to white as they get warmer and turn purple when exposed to uv. So the same print will look different in a hot sunny room in Rome—maybe white, powder-blue and purple—and a dark cold room in Norway—where it would be royal/navy blue and stark white. The prints show their experiences, their lives, and eventually the chemical reactions left in the ink will run out. I assume each print will ‘fix’ into a different final resting state eventually.

All artwork images courtesy the artist and Evelyn Yard, London. Photos: Sylvain Deleu