It’s 11am and Rana Begum arrives at her studio with two small and perfectly-formed children in tow. Her eight-year-old son greets me first, with a confident nod from under a mop of glossy hair, then Begum steps in, dressed in a yellow sweater and jeans, with yellow nails to match—the colour of optimists. Begum is definitely one of those, and when she talks about her work and what motivates her it’s often in superlatives. “I love the idea of blurring the boundaries between painting, sculpture, architecture and design,” she says—you can see this in her work, such as her recent winning entry for the Abraaj Group Art Prize, triangular slices of sheer MDF in a rainbow of colours as intense as the Dubai sun that beat down on them.

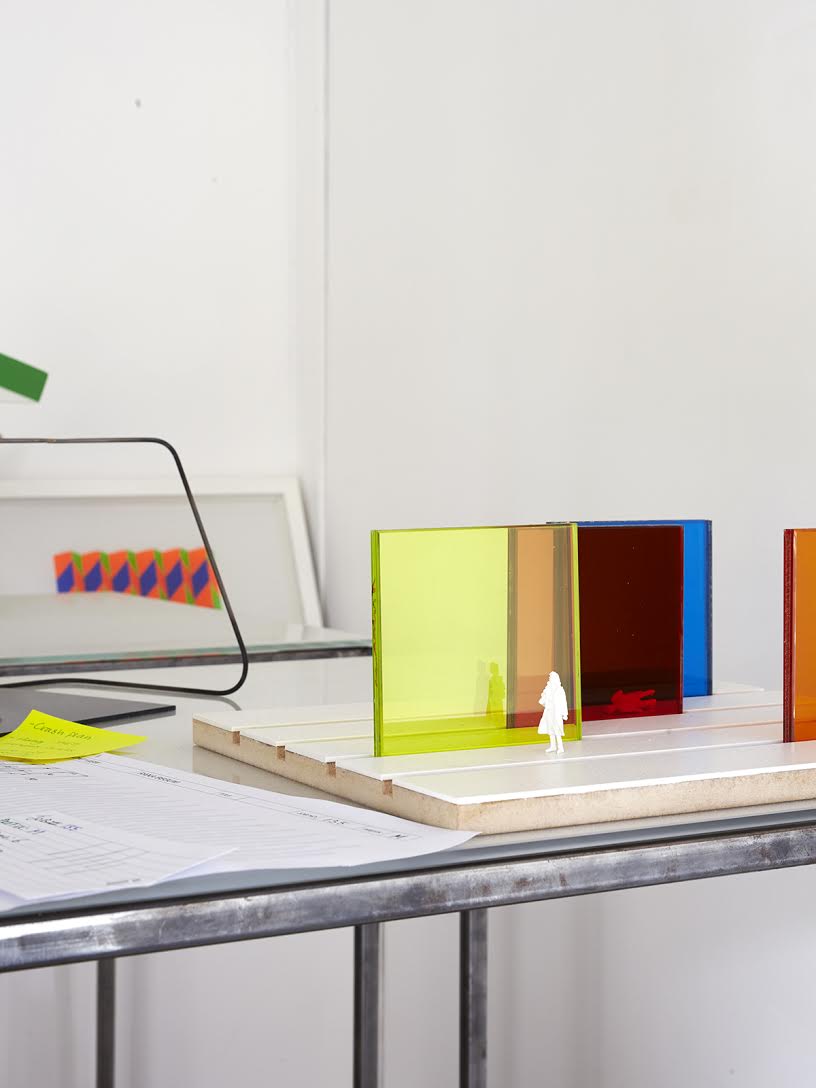

The many rooms of her two floor studio in N15 are all occupied with assiduous assistants, and the way the space is divided shows a lot about how Begum works: several workshop areas are filled with models, tools and tests, a separate room for testing out spray paint, while an office space is neat and organised, post-its on the wall. There is a technical, methodical aspect to what she does, but also plenty of space for play and accident along the way.

Begum is an abstract artist, but she doesn’t think like one and it wouldn’t be right to frame her work in the kind of theory that usually drips thickly over artists of her canon. Her process and its outcome are far more intuitive, creating environments where the viewer can experience something: a form, a line, a colour, a reflection of the light. Perhaps that’s why Nick Hackworth called her an “urban romantic”? She smiles bashfully. “I love living in a city, I love exploring cities and I love seeing things change and clash and come together. The city for me really brings all those things out.”

Around London, you might have seen her work on the side of Marcol House, on Regent Street, or at Lewis Cubitt Square in Kings Cross, but her latest project is far from her usual urban setting: an exhibition she has curated from the Arts Council collection at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, opened on 15 July. She is just as ardent when talking about that, and the work of the artists involved, from virtual unknowns to the likes of Mona Hatoum and Richard Wentworth (from whom she took the title for the exhibition).

Perhaps Begum’s bright demeanour is unsurprising: she works with light. It’s light that activates her work, and it’s light that she’s most interested in, and its infinite, galvanising energy.

You came to London from Bangladesh when you were eight. How have your early memories informed your aesthetic interests later on?

My memories of my childhood in Bangladesh are of light and these incredible views of the rice fields, the green lush colours. I remember arriving here in London in February 1985 and it was all white: there was thick snow and it was sunny, and I was really struck by the light bouncing off the snow, the brightness and the light–the warm glow to it. The difference of experiences is probably why a lot of things like that appear in my work, where you don’t have the same experience over and over again. I wanted that to be highlighted in my work.

What initially made you interested in abstract art?

I was doing a lot of figurative and representational work, which I realised I was kind of really struggling with, but then I got introduced to minimalist artists and abstract art and I was drawn to their work but couldn’t understand why, so I went back to my work and started making a list of what was exciting me: line, colour, form, all those things. It started to make sense. I wanted to understand where abstract art was coming from, but I knew I couldn’t go down the theory route because English was my second language and I struggled with it. So I decided to take a more practical approach to it.

How did you move from your early practice at Chelsea to your later relief type works?

I started to explore form and light, and how natural light changed the work throughout the day, and then other things, such as repetition, geometry, surface started coming into it. At first I tried quite hard with colour, but there were a lot of things that weren’t quite right. I came back to it in the second year of my MA at Slade. I knew I couldn’t use paint because I didn’t really enjoy mixing paint–it always ended up being muddy and murky. I realised I had a huge palette of colours, adhesive tapes I’d collected from my travels, so I decided to explore those. Even the thinnest strip of colour would change the mood of the work.

How and why have your materials changed over the years?

I started working with resin as a solution to make the work last, as people were interested in buying them, but it was so hard to work with. It was tough trying to get the surface perfect. I started to think about the sculptural aspect of the work, and how form and colour come together.

I then needed to move forward and find a new material I could work with, so I started to work with powder-coated aluminium, which returned in a way to my earlier work, looking at how light interacts with form and changes surface. I want the work to have some kind of movement whether it’s in the material or in people physically moving around the work. Now I work with various materials like perspex, stainless steel, copper, brass, aluminium, concrete and wood.

Your Instagram is kind of like a visual sketchbook of your ideas. How does photography play into your practice?

I’ve been taking photographs of things I see that inspire me for some time, and it’s strange because you perhaps don’t see a direct link but you can see some things that come through in the work in terms of capturing certain moments when the light activates the form and the colour. Photography has become a great tool to capture these moments.

And what about painting?

At the moment they’re research tools for me, they’re not the end product. I want the interaction to be much more physical, more of an experience, but the paintings explain to the viewer how the colours interact.

How did you start to create your colour mix “gradient” works?

It started in 2009, using aluminium bar pieces. I was focusing on movement, and how the work would change as the viewer walked from one side to another. What I hadn’t anticipated with that first work was that the colours would start mixing–it wasn’t planned, it was an accident! Initially I felt it was a disaster because I don’t mix colour, but it was for a show and it was too late for me to do anything. So I had to leave it, and the more I looked at it, the more excited I got because of the way it naturally mixed colour and produced a third layer of geometry. This process is still really exciting. We don’t paint gradients on at all–it’s all a result of the light.

Can you tell me about your Parasol unit installation, your first UK institutional show that took place last year?

That installation stemmed from my basket installation at Dhaka Art Summit, I wanted to use colour and movement in the work, but in a more structural way. As you moved around it, colours appear and disappear. It was the first exhibition that gave a broader understanding of work over the last fifteen years, until then my work had been shown in quite a fragmentary way. I always find it difficult that there has to be a narrative to the work, but I think it helped explain where it all came from.

On 15 July you unveiled your first exhibition as a curator, Occasional Geometries, at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. You said you looked for works that “have a soul”.

I wanted the exhibition to be a visual experience of the work itself, so I made a conscious decision not to look at the titles of works or artist names at first. I wanted there to be something that lingered–the experiences you have walking down the street, seeing things change and shift. That’s where I felt you could really get the viewer engaged and get them to understand–something that reminded you of the day-to-day aspect of one’s life.

How did it go?

You know, when you show your own work, you’re not as conscious of your position. When you work with someone else’s work it’s very different so I was really nervous, but I wanted a challenge. It was an amazing opportunity to work with the Arts Council collection, but I also wanted to show how it’s also still very relatable to what’s happening now, so 40 per cent of the works come from outside the collection. I absolutely love YSP, I’m in awe of it and they have a fantastic team.

How did you connect with some of the younger artists you selected?

I found quite a few of the artists on Instagram: Ayesha Singh, Nicky Hirst, Charlotte Moth.

Is that kind of connection with other artists, especially younger artists, important to you?

I think it’s really important, I think this highlights how important it is not only to support younger artists but to see how ideas are still being developed and refreshed by a younger generation, we’re speaking the same language but it’s different. I’m really into having my work in group shows, I love seeing connections with other artists, it’s beautiful to see how one work speaks to another.

Photographs © Tim Smyth.