Scotland, Rachel Maclean

Maclean is a pertinent choice for Scotland, considering her numerous works which tackle the politics and cliches of the country itself—as well as the wider United Kingdom—including hyper video pieces such as The Lion and the Unicorn and I Heart Scotland.

Her new video installation Spite Your Face shows at the Biennale this year. As Maclean says herself of the work: “With this new film I set out to respond to significant changes in the political climate in the UK and abroad over the last twelve months—in particular the divisive campaigns in the lead up to the Brexit vote and the US Presidential Election. These events have been central in heralding a new post-truth era.”

Argentina, Claudia Fontes

Another politically-led artist, Claudia Fontes—who was born in Argentina and is currently based in the UK—has previously addressed the aggressive history of the country’s military regime. Her sculptural works are large-scale and gutsy, typically, intricately formed and presented in brilliant white.

Fontes is showing a five-metre-high horse sculpture at her home country’s pavilion. Entitled The Horse Problem, the installation in full features a horse, a woman and man responding (and frozen in that moment) to an event. The artist aims to tackle Argentina’s murky past and, in relation to the piece, she has discussed the damaging relationship that the domestication and industrialization of horses has had on humanity as it has enabled the creation of frontiers.

Romania, Geta Brătescu

Geta Brătescu was born in 1926 and worked for a large proportion of her practice within a communist state during Ceauşescu’s totalitarian regime. However, she has always treated the space within her studio in Bucharest as a place free from politics. Many of her works over the years—which have ventured into drawing, collage and photography as well as performance and tapestry—have addressed ideas of identity.

There are pieces from multiple stages of the artist’s practice represented in her pavilion show, Apparitions, which centres around two key themes: the studio and female subjectivity.

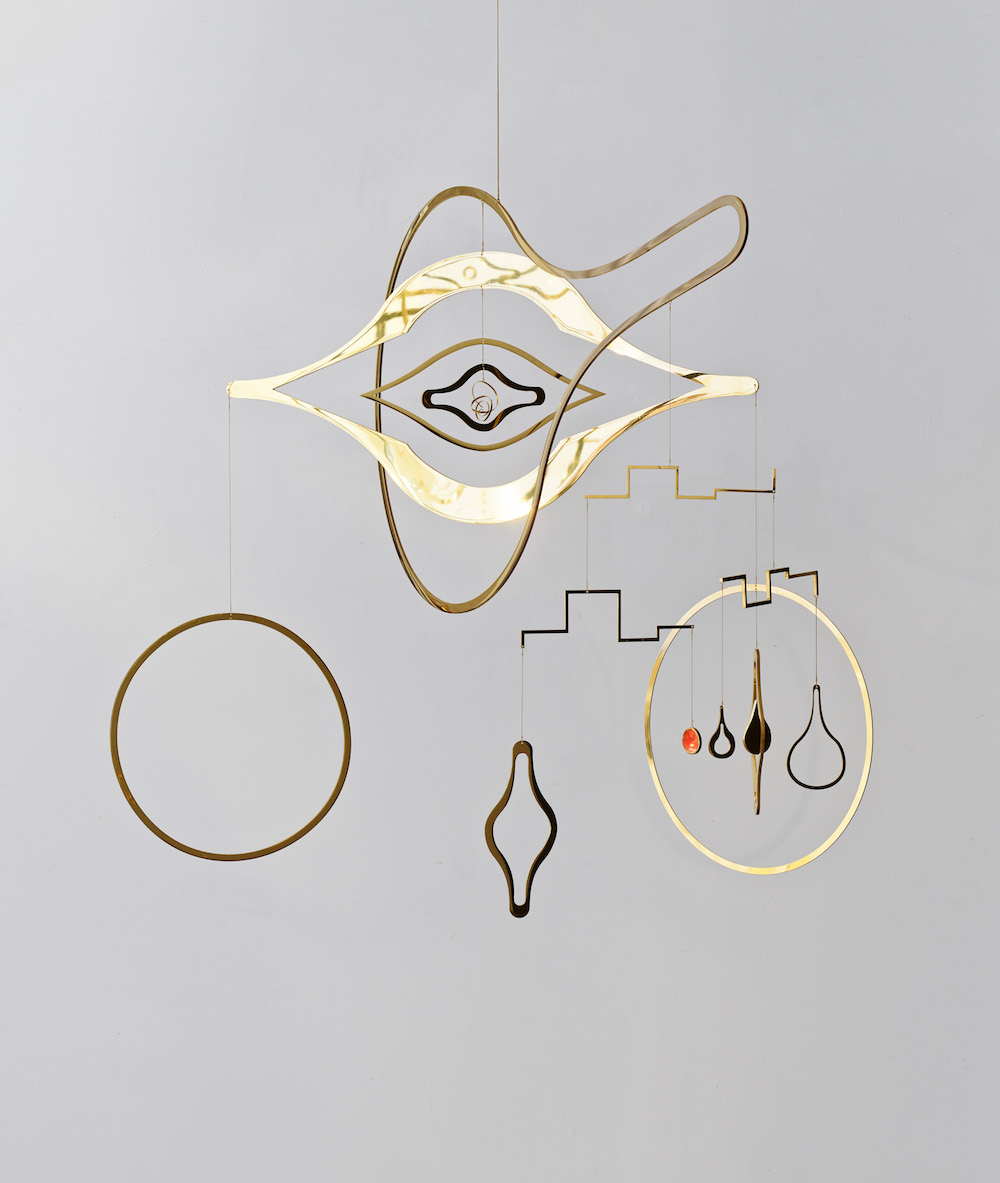

Czech Republic and Slovak Republic, Jana Zelibska

Jana Zelibska’s most recognized works feature the female body presented in a playful, potent and exploratory manner. In Kandarya – Mahadeva (1969) a diamond shaped vagina is cut from a large female figure on the wall in a room-sized installation and surrounded by pink and white flowers. In Breast I (2016), a breast sits mountain-like in close up.

For Venice, the artist presents a ‘pond’ of luminous swans in Swan Song Now, sitting in front of a large turquoise projection of the sea which was filmed in Venice. The swans are surrounded by other forms, notably, a piece of drift-wood from the Danube river which is covered in gold foil and further highlights the tension between the natural and the artificial. Nonetheless, the artist’s message is not wholly pessimistic. “Rather than being a commentary on an abject condition it challenges us to reflect and to hope,” she says.

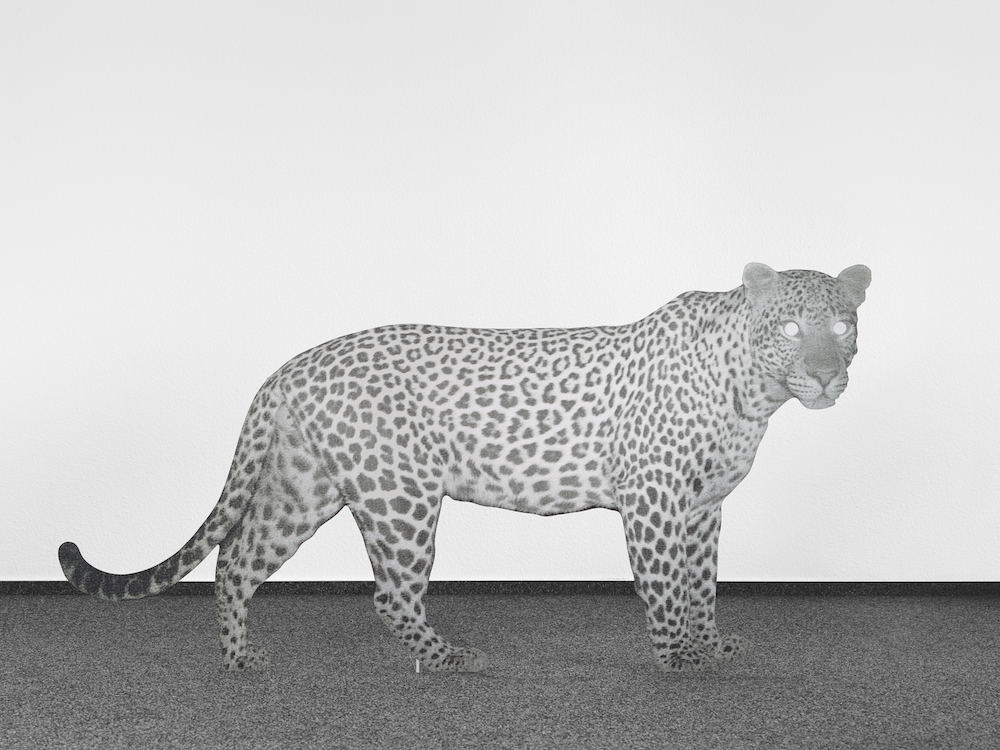

Estonia, Katja Novitskova

Estonian artist Katja Novitskova currently works between Berlin and Amsterdam and is engaged in debates around information systems and the digital world; so much so, that in 2011 she published a book for artists, the Post Internet Survival Guide.

She takes the title for Estonia’s Bienniale presentation from a Bladerunner quote: If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes. The exhibition looks at industries which are driven by data, and the relationship this has with seeing in the traditional sense. It also explores the potential this offers to map in ways beyond the geographical and the entirely new visual languages that are created along the way.

Denmark, Kirstine Roepstorff

Kirstine Roepstorff’s practice often explores power relations and the historical failure of certain political ideas. This, however, is a rare pavilion which makes lightness of dark times.

The artist’s influenza. theatre of glowing darkness invites viewers to experience darkness as a healing force and a place for “transformation and empowerment”, and also plays with the double meaning of “influenza”—meaning a terrible flu in many languages, but “to influence” in Italian. The large-scale installation utilizes not only darkness but also light projections, glass, sound and recorded dialogue, altering the form of the pavilion building itself.

Germany, Anne Imhof

Anne Imhof knows how to make an impact—her dramatic performance Angst II (filling Hamburger Bahnof with smoke and chiselled cheekboned performers) during 2016’s abc had everyone talking. She’s an obvious and excellent choice for Germany. For the Biennale she presents Faust. Already there are reports of the four caged Dobermans which guard the front of the pavilion and bark dramatically at the water spurting from Canada’s nearby pavilion. Inside, the performance totals five hours with multiple performers, including Imhof, engaging in movements both intense and throw away.

“The individual movements and gestures stand in contrast to the uniform flow of motions—remote-controlled via text messages—that are reminiscent of social codes,” reads the adjoining text, “continuously internalized without reflection.”

Andorra, Eve Ariza

Ariza has a dual practice, focussing on sculpture, typically using clay, and producing happenings. Throughout all of her work, the artist aims to combat the self-described “BLAH”, seeking to address the lack of truthfulness in human communication.

For the Biennale she presents Murmuri. “I decided to put myself in the hands of the clay and a potter’s wheel for several months to shape murmurs, one by one, none of them the same, and listen to them,” she says. “Clay has a voice and talks to us. I listen to it, to them. You are one; it is the other. We are all represented in it… My intention is that each murmur should resonate with the world through the Venetian experience. Everything is very simple, like the wheel that turns.”

Nigeria, Peju Alatise

This will mark the first year for Nigeria at the Venice Biennale, and they address their new inclusion within the event with the title How About Now?. As mentioned in their official description of the exhibition of their wider recognition within the art world: “There’s arguably no fitting reflection of our nation’s cultural progeny.”

For their debut, the Nigerian Pavilion will show the work of three different artists, including Peju Alatise. The artist is primarily known as a sculptor who addresses the role of women in society, and she is also a poet and writer. The life-sized human sculptures which comprise her Flying Girls at the Biennale addresses the life of child housemaids in Lagos and imagines a safer future.

New Zealand, Lisa Reihana

Reihana has a materially wide-reaching practice which includes live-action, costume, photography, film and sound.

In Lisa Reihana: Emissaries the artist presents multiple pieces, the most prominent of which is 2015-17 panoramic video work in Pursuit of Venus [infected] which reimagines Les Sauvages De La Mer Pacifique (the French scenic wallpaper from 1804) with the use of digital technology, seen through Pacific eyes. The narrative moves from the real to the fictional, touching on known moments as well as invented stories, and includes dance and cultural ceremonies which represent a range of people from New Zealand and the Pacific.

South Africa, Candice Breitz

After a potent opening at KOW during Gallery Weekend Berlin—Love Story, a large video installation which explores the refugee crisis and the roots of empathy from multiple locations—Candice Breitz shows alongside Mohau Modisakeng at South Africa’s pavilion, addressing the idea of selfhood within a global world that continues to marginalize many. The work of the two artists is placed here in dialogue.

“Breitz’s photographs and multi-channel video installations offer nuanced studies of the structure of identity under global capitalism,” says one of the pavilion’s curators Lucy MacGarry, “while Modisakeng employs a highly personal language to express ideas about his own identity and the body.”

Australia, Tracey Moffatt

Tracey Moffatt is most recognized for her film and video work, which often moves into documentary. Since graduating in the early eighties, the social and cultural understanding of Aboriginal people in Australia has been a focus for the artist, and the human being and life is typically front and centre of her work.

For the Biennale, the artist presents MY HORIZON, which comprises two new large-scale photographic series–Body Remembers and Passage–and two new film works–Vigil and The White Ghosts–which contain constructed narratives. “I have taken my camera into unknown locations and created photo-dramas,” Moffatt says of the exhibition. “My stories meld fiction, fact and some aspects of my family history. MY HORIZON can represent a yearning for escape to another place.”