When I was a child, my dad, a builder, used to make mini “house foundations” for us in empty plastic meat boxes. When working on an extension he’d pour, layer by layer, the different elements of the foundation into the box so we could see a cross section of all the materials. Maybe this only happened once, but it stuck with me. It was satisfying seeing these different materials—greys and dirty peaches—squashed up against one another, and to hold this smallish box and feel we could understand, from this, the stability of the entire building we were standing in.

I had a particular wave of joy and nostalgia, then, on discovering Holly Hendry’s work, as many now have, since the artist graduated from the RCA this summer. She’s off to a good start, with a solo show at BALTIC in Gateshead which will run into the autumn, inclusion in a group show at White Rainbow gallery in London this March and representation from Limoncello gallery.

Her works often employ building materials. Despite the personal enjoyment that this brings me—the same I feel when I walk into a freshly painted or plastered room and think, for a moment, of swinging my feet over the side of a low-set scaffold board while my dad whistles along to the radio—there are many universal connotations to be found here; from the insides of the body to the unkempt world hidden behind our cleanly designed interior facades.

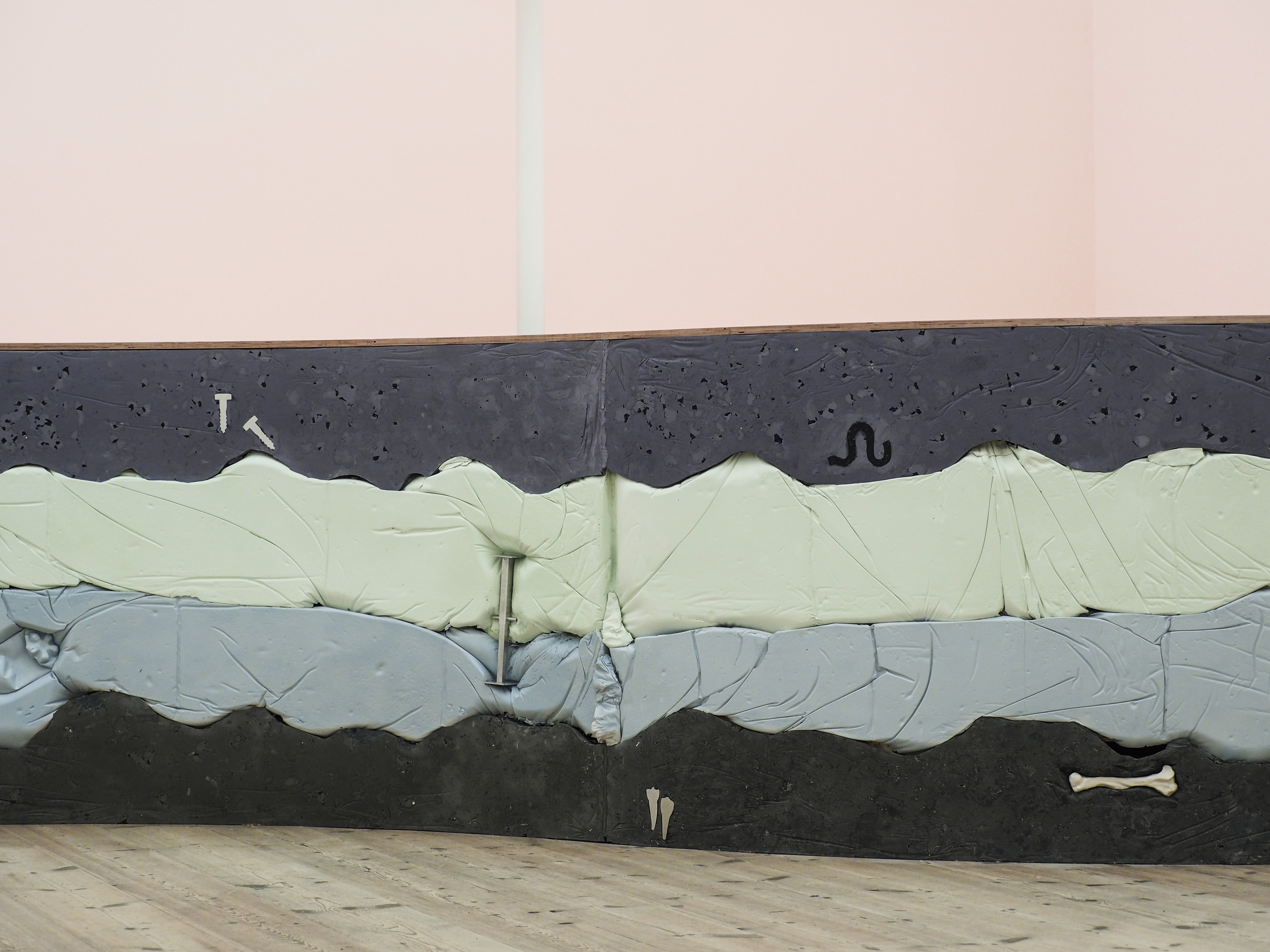

The work is undeniably aesthetically pleasing, a mix of beautiful metallic lilacs and pinks with materials such as cement, birch ply, soap and rawhide dog chew. Scale is another important aspect of Hendry’s work, as her cross sections in particular link not only to the stuff found in walls and under floors, but also to the micro world; school diagrams of plants and layers of skin. The shapes are organic and rough in places but there’s also a precision which suggests a huge level of design, as with these biological forms.

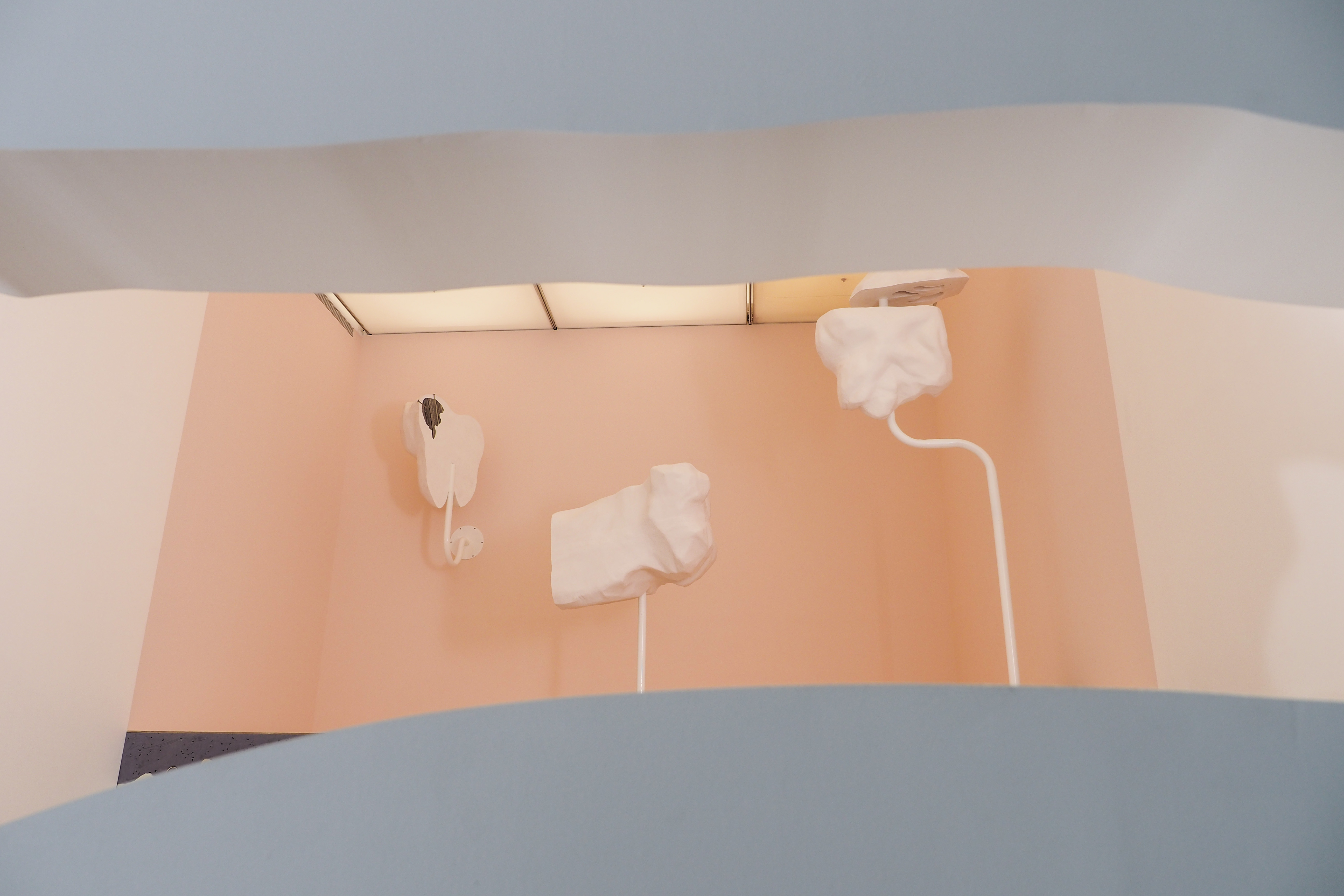

Wrot, an installation which fills a single room on the second floor of BALTIC, is an especially refined example. A wave of signature cross section—greys, blue and greens punctuated at points with objects such as bone forms and nails (the metal kind, not the finger kind)—sits at the back of the room, underneath a group of large, square light panels, and is enclosed by three pale pink walls. Three white structures rise above the stage-like platform, offering a sense of formal “above” and messy “below”. On the opposite wall, a bone shape is cut out of the wall which further impresses these ideas of what is seen and unseen, what is fit for consumption, and what is hidden away. It allows the viewer to peek in from the other side of the wall and see only a section of this installation, or to gaze out at a section of BALTIC’s enormous lift shaft and city view. Leaning against the wall inside the room is a large bone shaped form, layered and reconstructed where it looks as though it has cracked. It looks like this piece could be picked up and slotted straight back into the hole in the wall, as big coloured wooden shapes are on children’s interactive toys.

“Physically, the show plays with variations of surfaces and planes,” says Hendry of the piece, “raising one section of the floor to make a slightly stage-like setting where boney sculptures tower above, and cutting a hole in the wall so that sections of outside are viewed from within, and vice versa. There’s a shifting of macro and micro where visitors are brought up close to the forms that speak of the underneath–whether that is under our feet or under our skin, it’s a closer look at impressions of objects, bodies and ‘stuff’.”

‘Wrot’ is showing at BALTIC, Gateshead until 24 September. All images: Holly Hendry, Wrot 2017. Installation view at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Photo: Mark Pinder/Meta-4